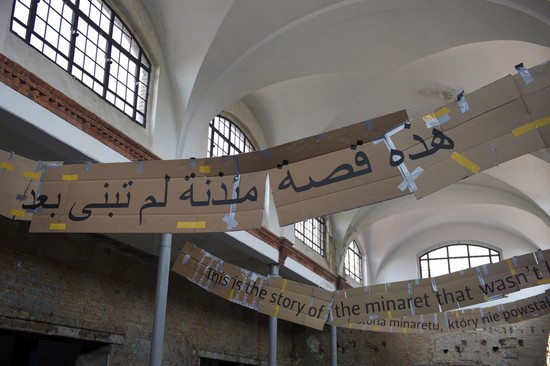

This Is a Story of a Minaret that Never Happened

July 7, 2011,

A day of meetings, presentations and talks to complete over two years’ work on Joanna Rajkowska’s Minaret project

Stara Rzeźnia, Poznań

‘What is absolutely crucial for me is the relationship between the work, a real work in real space, and the body. One can hardly discuss a project’s impact on the public sphere if the project is not physically there, if everyone only imagines how it would look like. Minaret is not there. Poznań will not see it. Everything else matters a lot, but not for the life of the city, which, in its substance – evolving, ageing, fluid – has remained unchanged.’

Joanna Rajkowska

This Is a Story of a Minaret that Never Happened is a series of projects completing over two years’ work on the Minaret project.

The title is not a provocation, rather an admission of failure and lack of hope for making the Minaret come true in Poznań.

Idea of Joanna Rajkowska’s Minaret Project

The original project provided for transforming a defunct smokestack of a former paper mill located at the junction of Estkowskiego Street and Szyperska Street in downtown Poznań.

The smokestack stands in the middle of an area of chaotic development that has a ‘Middle Eastern’ feel about it, on precisely the same viewing axis as the Poznań cathedral on the Ostrów Tumski island. An Interactive Centre of the History of Ostrów Tumski is to be launched here by 2012, its aim to promote the place as the cradle of Polish statehood and Christianity in Poland. The line then leads towards Małe Garbary Street and Stawna Street by the Old Market Square, where stands the former synagogue, converted in 1940 into a swimming pool for Wehrmacht soldiers and functioning as a swimming pool ever since.

The Minaret’s architectural form was to be based on the design of the minaret of the Great Mosque of Jenin in the West Bank of the Jordan River, one of the earliest masterpieces of Ottoman architectures in the Palestine.

Just like the palm tree in Warsaw (Greetings from Jerusalem Avenue), so the Minaret was to become a permanent feature of the city’s landscape, lending the site an illusive, surreal and exotic feel.

It is 2011, the third edition of the Malta Festival as part of which the Minaret project is being presented and discussed. In both 2009 and 2010, there was determination in us and faith in the project’s eventual success. In discussion panels accompanying the Festival in those years, we successively announced plans for the following:

– constructing a stone Minaret (in 2009 we naively believed that such an object would be constructed next year, a belief backed by support from Poznań Vice-President Maciej Frankiewicz, who unfortunately died tragically soon thereafter);

– inaugurating a temporary light installation of the Minaret’s outline (in 2010 we were already aware of the city’s negative position on a permanent Minaret installation, but we still didn’t know enough to doubt the possibility of creating a short-term visual intervention);

– implementing in Poznań’s high schools an educational programme on multiculturality, inspired by the Minaret project (only a year ago we believed the sincerity of Vice-president Sławomir Hinc’s pledges, so we assumed the pilot stage of the programme would kick off as early as in January 2011).

None of these plans and pledges have come true. The Minaret, whether permanent or temporary, was blocked on the political and administrative levels by the city authorities. The Education Department did not find the readiness to finance and implement the planned educational programme.

Writing this (in May 2011), we still hoped (falsely, perhaps) that we were wrong about the LED-light Minaret installation having been blocked and that the Minaret ‘architectural drawing’ around the smokestack would come to life during the festival nights, that we would hear the voice of a muezzin resounding from there at the project’s inauguration.

In our view, it was an appeal for opening towards the Muslim minority, towards religious and cultural alterity, but also for a fresh look on the city, its architecture and the overwhelming impact and influence this architecture has on the city’s and its inhabitants’ identity formation.

An appeal, therefore, for a critical review of the seemingly neutral shaping of the city’s public space. For examining the values and interests supporting the process – which was also behind the decision to block the realisation of the Minaret public project.

It would seem that the decision was made in the name of the image of Poznań and its inhabitants’ collective ‘self’ – as shaped by the city authorities, based on national and religious unity. What the city hall seems not to notice, however, is that this monolithic collective identity has been losing currency and is no longer obvious or shared by everyone in the city. In Poznań’s current social situation, stabilising or reinforcing it may result in violent exclusions of some of its residents. This is a real and significant danger.

Although the Minaret did not happen, the very vision of it proved powerful enough to provoke a heated public debate. Strong emotions were expressed both by the city’s residents, including members of the Muslim community, and by its officials, as well as by the local, regional and national media and members of the public. The divisions that became evident in the process cut across extant demarcation lines in the city. The Minaret raised a number of difficult questions not only about the city’s desired shape and its residents’ identity, but also, more broadly, about the Polish and European attitude towards Islam, questions that have never been asked so emphatically in the Polish public discourse so far.

These questions are tackled from an interdisciplinary perspective on the project’s website http://www.minaret.art.pl. The site will remain active despite the conclusion of the installation project.

The Minaret Effect: events during the project’s run-up phase

2009

Malta Festival, discussion panel, Minaret. Around Joanna Rajkowska’s Public Project in Poznań, the project’s first public presentation

2010

Malta Festival, The March Backwards, street action initiated by Hanna Gill-Piątek, ‘from the most real cathedral, under a yet-nonexistent smokestack-come-minaret, to a synagogue-come-swimming pool’

Malta Festival, The Minaret Effect, discussion panel outlining a planned educational programme on multiculturality

The Chariot, or, a Postcolonial Vehicle, seminar with Joanna Rajkowska, Questions of Boundaries Research Group, 22 April 2010, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań

Presentation of the Minaret project during the group exhibition Hostpitality. Receiving Strangers, curator Jarosław Lubiak, Muzeum Sztuki, Łódź

‘Analysing Islamophobia’, conference, Instytut Studiów nad Islamem, Wrocław; papers (including a paper on Islamophobic reactions to the Minaret) to be published in 2011 by Instytut Wydawniczy “Książka i Prasa” under the patronage of the Polish edition of Le Monde Diplomatique

2011

New issue of Nowa Krytyka ‘Postcolonialism. Joanna Rajkowska’ devoted to postcolonialism and Joanna Rajkowska, cover text by Monika Bobako and Dorota Grobelna, ‘Philosophy, Colonialism and a Minaret that Never Happened’

Turning points in the history of the Minaret project

September-November 2008

Joanna Rajkowska’s artistic residency in Poznań, development of the concept of the Minaret project, as provided for in the official agreement: ‘From 23 September to 20 November 2008, artist Joanna Rajkowska, hereinafter referred to as the Contractor, shall reside in Poznań at the invitation of the City of Poznań in order to develop a public-space project for the city’

June 2009

Negative opinion of the Competition Jury (on which sat, among others, the Deputy Director of the City of Poznań Department of Urban Planning and Architecture, the Municipal Conservation Officer, and the Director of the Municipal Housing Property Management Board, which manages the plot on which the smokestack stands):

By the way, the Competition Jury deems it appropriate to publicly voice its firmly negative opinion about the idea of turning the existing industrial smokestack of a former paper works into the form of a minaret.

The Competition Jury believes that the project:

a) is culturally alien;

b) interferes with views of the cathedral and the nearby building of a former synagogue;

c) could be interpreted as a religious provocation;

d) could be interpreted as an attempt to ridicule a religious symbol – the minaret – by locating it on an industrial smokestack;

e) has no important artistic values related to cultural events in the city of Poznań.

December 2009

Letter from the Municipal Conservation Officer: The smokestack is ‘located within the listed urbanistic/architectural complex of the Poznań city centre’, ‘within an area recognised as a Historical Monument’, and ‘en route from the old town towards Ostrów Tumski’.

‘The purpose of protecting the said historical monument is to preserve, due to its historical, urbanistic, architectural and intangible values, a historical part of the city and the original condition of the whole area, and all interventions in those are inadvisable from the conservation officer’s point of view. The City Conservation Officer accepts various kinds of artistic events on the condition, however, that they are of a temporary nature rather than as permanent features of the city landscape. From the Conservation Officer’s point of view, a permanent alteration of the smokestack’s character is unacceptable…’

December 2010-June 2011

Letters from the Municipal Housing Property Management Board refusing permission for installing a temporary ‘light installation’ on the smokestack

The Minaret at Malta Festival 2011: This Is a Story of a Minaret that Never Happened

Stara Rzeźnia, 7 July 2011, 11.00-20.00

An exhibition of visual materials created during the work on the Minaret project, documentation of actions undertaken as part of the project since 2009 and of the project’s public reception, and a tentative interpretation of the project and its reception

A series of meetings: with the project’s author, Joanna Rajkowska, and the Minaret team, the project’s producer, Malta Foundation, persons, institutions and organisations involved in the project, and invited guests. We are also hoping for the participation of City of Poznań officials

Presentation of the new issue of Nowa Krytyka: ‘Postcolonialism. Joanna Rajkowska’, featuring projects by Joanna Rajkowska, including the Minaret, besides texts discussing various issues of postcolonial theory (constituting an expanded version of Postcolonialism as a Critical Discourse, a 2009/2010 lecture series of the Adam Mickiewicz University’s Questions of Boundaries Research Group)

Presentation of publications devoted to Joanna Rajkowska’s public projects.

The Minaret team

Joanna Rajkowska – author of project

Dorota Grobelna – curator

Wiktoria Szczupacka – documentation, website editor

Stefan Bajer – architect

Hanna Gill-Piątek – author of The March Backwards (2010), collaboration on exhibitions

Mateusz Witkowski – graphic design

Rafał Żurek – camera

Before:

Jakub Dąbrowski – initiator and co-organiser of Joanna Rajkowska’s residency in Poznań, during which the idea of the project was born

Katarzyna Czarnecka – coordinator of cooperation with Krytyka Polityczna, collaboration on fundraising

Tomasz Osięgłowski – architect

Project produced by Fundacja Malta

Exhibition produced by Fundacja Malta and Poznańskie Stowarzyszenie Inicjatyw Teatralnych

Exhibition co-financed by the City of Poznań

Partners: Adam Mickiewicz University Questions of Boundaries Research Group, Instytut Studiów nad Islamem, Poznańskie Stowarzyszenie Inicjatyw Teatralnych, Muzeum Sztuki Nowoczesnej, Krytyka Polityczna, Le Monde Diplomatique (Polish edition), Nowa Krytyka, Fundacja Wiedza Lokalna

Sponsor of Artist’s trip to Jenin: Anadolu Kültür

Realised as part of a Minister of Culture and National Heritage grant (for the Curator)

Education programme expert team: Prof Wojciech Burszta (head), Karolina Białek, Izabela Czerniejewska PhD, Piotr Majewski, Agata Marek PhD, Jacek Schmidt PhD, Karol Wittels

Neither the Minaret nor the planned educational programme have been realised, due to the negative opinion of the City of Poznań authorities and the City’s withdrawal from collaboration on those projects.