Regenerate Art

11 October – 30 November 2014,

group exhibition at Künstverein München

Künstverein München e.V., Munich, Germany

Group exhibition of variant public art proposals, satirical reflections and unmade commissions

For this exhibition, variant public art proposals, satirical reflections and unmade commissions are brought together to address different notions of regeneration within ongoing discussions over the role of art in the public realm. By confronting the structures that shape our built-up environment, the artworks in ‘Regenerate Art’ considers unrealisation as means of artistic production, intent or negotiation.

Such hypotheticals tend to reveal the circumstances and conditions involved in commissioning processes, which often determine what art appears in the public realm. In particular, the works in this show speculate upon the machinations behind the regenerative prospect of public art, whether from the point of view of an artist or a fictional viewpoint of a commissioner. Each of the projects are characterised and informed by the specific contexts of their localities in regions of Germany, Estonia, the Balkan states, and England, when public art is incorporated in urban planning as a strategy to build capital, aesthetically problem-solve or vitalise areas in need of redevelopment. As such, ‘Regenerate Art’ creates an alternative reality where public art profoundly reflects its surroundings, in which artists respond to criteria such as the privatisation of the public sphere and artistic instrumentalisation within neoliberal cultural policy.

Furthermore, the exhibition demonstrates how artists have, sometimes humorously, interpreted or critically engaged with ideas of ideology and form in public art. For example, where Lukas Duwenhögger’s unrealised proposal for a memorial remembering homosexual victims of National Socialism questions the very appearance and aesthetic decree of what constitutes the monumental, Aleksandra Domanović’s film-essay Turbo Sculpture frames a recent Balkan phenomenon of civic sculpture based on Western pop cultural figures rather than traditional heroic effigies in so-called ‘post-ideological’ societies. In this respect the exhibition is aesthetically charged – purposefully emphasising the visual over archival material and documentation, to illustrate applied meanings of regeneration, whether of urban space, through cultural healing or in relation to the body.

Saim Demircan

———————————————————————————————

Excerpt from the ehibition catalogue

In early 2011 the former mayor of Detroit Dave Bing was publicizing a citywide redevelopment initiative called Detroit Works Project on Twitter. One commenter responded by suggesting a statue of Robocop, to which Bing politely (yet curtly) dissolved.[1] But not before the idea went viral, eventually resulting in a kickstarter campaign that successfully fundraised above the projected cost to realize the proposal.[2] Why did this idea gain such traction though, considering the original 1987 film is a satire of Regan-era corporate politics, gentrification and privatization? Given the context of this film, Robocop seems like an unlikely ambassador for Detroit, even in regard to other fiction-based statues such as the Rocky Balboa statue in Philadelphia, who have come to symbolize the cities where these characters were based.

Paradoxically, one can also see how Detroit has started to resemble the fictional near-future city as portrayed in Robocop. For example, the relationship between urban planning and business are conspicuous in real world examples today. In the film the mayor of Detroit makes a deal with a corporation to bankroll the city’s cash-strapped police department, while earlier this year several businesses leased the police a squad of 25 new cars in a deal formerly brokered by Bing.[3] Even the image of the fictional Delta City – a proposed company-run Elysian in Robocop – sounds not unlike the Future City currently being suggested as part of Detroit’s new blueprint.[4]

In a sense, Robocop is symptomatic for such a dystopian example of a post-industrial city struggling to regenerate after a healthy period of production. So perhaps the image of a corporate-sponsored machine cleaning up the streets of Detroit can be seen as an apt heroic effigy, in that it is a profound reflection of its surroundings. How then does public art truly respond to the specific contexts it is proposed for if the regenerative potential, as heralded by this statue for instance, can be considered metaphorically? ‘Regenerate Art’ hypothesizes on this as a theme, through public art proposals, satirical reflections and unmade commissions, which confront either regeneration projects they have been conceived for or propose reflective responses to the commissioning of public art.

The fictional and its real-world parallels in Scott King’s Anish and Antony Take Afghanistan for example are trenchant; with global leaders standing in for city officials, commissioning bodies and local developers and a region replaced by conflict in the Middle East. While its message reads in a similar vein to that of preemptive dystopic fiction – the narrative arc is a vicious loop resulting in a reverse-9/11 – his satirical take on artistic intrumentalisation can be seen in relation to Kapoor’s winning public art proposal – a gigantic sculpture/viewing platform hybrid for the Olympic site in the east end of London.[5] King exaggerates how the artists are blind sighted by ambition, yet in reality Kapoor’s own aspirations were also seemingly driven by scale, un-ironically citing the Eiffel Tower and the even the Tower of Babel as references.[6] In one of the panels from Anish and Antony Take Afghanistan, Kapoor can quite literally be seen (orbiting) above the earth, building a similar version of the ArcelorMittal Orbit in space. Back on the ground however, the artist’s intent thinly-veiled a merger between urban planning and business, as the majority of the structure’s funding was donated by Indian steel magnate and Britain’s richest man, Lakshmi Mittal through a tête-à-tête with Boris Johnson, the major of London.[7] Most obviously, its title, ArcelorMittal Orbit, is flagrantly prefixed with the company name.

In this case the form that public art takes not so much reflects it surroundings, rather the corporate dealing and political narcissism that made it appear in reality. Whereas the motivations behind ArcelorMittal Orbit determined the outcome of the proposed structure, on the other hand the aesthetics of Lukas Duwenhögger’s competition submission for a public memorial to commemorate the persecuted homosexuals of National Socialism in Berlin were questionable within the context of a memorialising object. ‘To honor the dead properly, we were told, we must surrender our democratic right to critical speech and subjugate ourselves to official discourses of truth’, wrote Rosalyn Deutsche recently in her analysis of the completed September 11 Memorial Museum in New York City.[8]

Duwenhögger’s proposal could likewise be thought of in similar terms. After it was initially rejected, the artist later remarked that the apprehension of the commissioning body towards his proposal contradicted some of the very sensibilities of the people they wished to commemorate.[9] Perhaps because The Celestial Teapot responds to what Roger Cook identifies as an absurdity that disturbs.[10] While it displays no obvious outward appearance of being a memorial, traditionally speaking, Cook considers a crucial trait in Duwenhögger’s proposal – that of humour and its deployment as a serious judgment. ‘Homosexuals have often responded to oppression with humour; this is at the root of the sensibility known as ‘camp’’, writes Cook. The artist’s ‘teapot is far too effusive, beautiful and self-evident to succeed as a proposal for an architectural challenge occupying the high moral ground of an antifascist monument’, making the impossibility of Duwenhögger’s idea perhaps worth protecting instead.[11]

While its integrity maybe an efficacious quality of Duwenhögger’s proposal as an artwork derived from a public art project, it also represents more broadly how, conceptually-speaking, unrealisation raises moral issues that the regenerative prerequisite of art in the public realm sometimes has difficultly reconciling with. Similarly, although on the receiving end of a commission, Joanna Rajkowska’s The Peterborough Child is as much about personal healing and rejuvenation as it is about a geographical, historical site. The artist’s project was withdrawn involuntarily in its penultimate stage due to religious objections from members of the resident Islamic community. Because of these outspoken remarks, which were in fact extraneous, the town’s local authorities swiftly bypassed their own regulations in order to effectively cease any further progress with the project. However Rajkowska suspects a legitimate reason behind its cancelation was in part because of Peterborough’s high infant mortality rate, and her proposal touched a very real nerve in the eyes of the local authorities. Yet the emotional honesty in her retelling of the process sits in stark contrast to their denial; firstly to provide the artist with more than the intangible reasoning behind the cancelation of her project[12] and secondly to interpret a repressed social anxiety that was revealed through its very proposition.

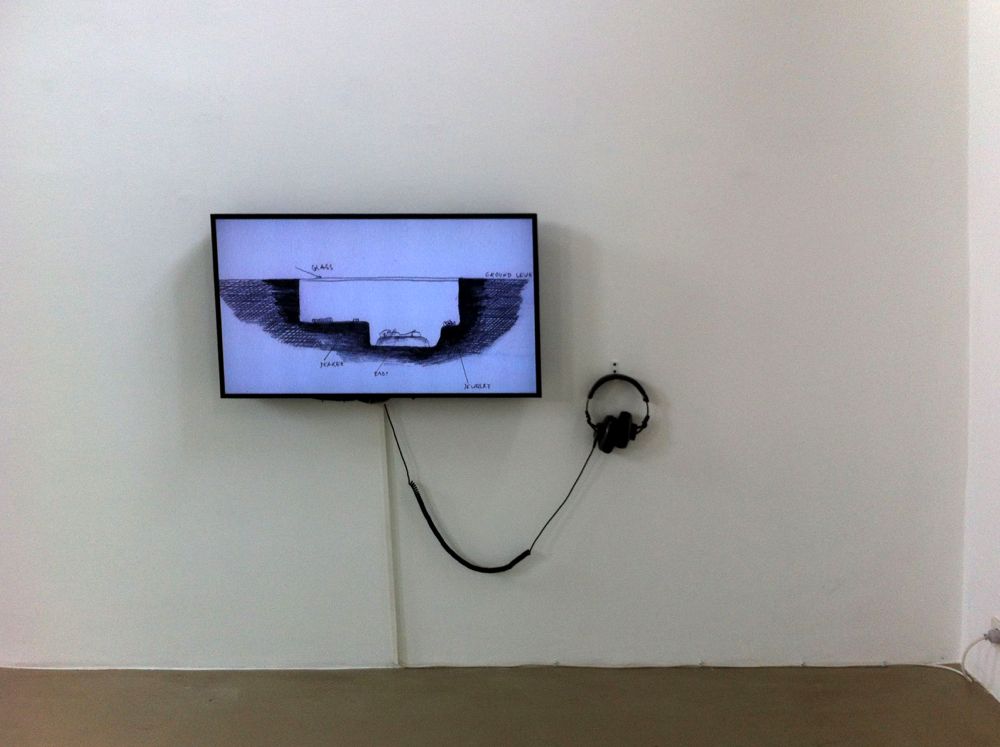

In this respect – as with Duwenhögger, who continued developing The Celestial Teapot over several years – the unfamiliar proposal becomes a starting point for artistic production. Speaking about The Petersborough Child after the project was cancelled, Rajkowska raises an important point in that, ‘this is actually the moment where real negotiation and participation should start.’[13] In silencing it before it had chance to enter the public realm, the artist realised that her proposal could in fact be the beginning of a discussion. By transferring the story of The Peterborough Child to the fictionalised form of an animated film – the work that Rajkowska produced from her proposal, which is shown in the exhibition – the artist is able to analyze the circumstances around the project as a form of catharsis formally denied to her. Yet its unrealisation also represents a negotiation between an artwork and a specific context as a point of reflection, reinstating Josephine Berry Slater and Anthony Iles’ rhetorical question that, ‘should we not rather consider aesthetic experiments in terms of tensions they establish with their contexts and the forces which attempt to direct them?’[14]

While this new artwork reflects the surroundings of The Petersborough Child after it was cancelled, Chris Evans on the other hand becomes an instigator, agent or consultant as a starting point in his practice, whether proposing a sculpture park in Estonia or offering a British Socialist newspaper a free redesign. What might appear to be incongruous pairings or even absurd propositions in the works Radical Loyalty and Morning Star Rebranded, can in fact be considered as logically reconciling ideology and form through commissioning or rebranding strategies. Several artworks in ‘Regenerate Art’ also reverse the top-down structure, often humorously, by adopting a fictitious viewpoint of a commissioner. For example, in making their work, Alan Kane & Simon Pertion considered public art as a genre to be subverted, deliberately using the proposal is a means to deflect the slow processes that normally determine the realization of public art. [15]

What these and all the projects in the exhibition show is a mirroring of applied meanings of regeneration in public art. Effectively, the artists in ‘Regenerate Art’ turn the public art proposal – whether rejected, unsolicited or a hypothetical reflection – into a new work or analysis of their public and political contexts. So instead of becoming lost or unconsidered, it is the beginning for works that are affirmative reflections of urban regeneration, cultural healing, ideology and form. Perhaps policy makers could benefit from considering unrealised, speculative, or even absurd proposals as a way of seeing an alternative reality of public space as its currently being governed.

Whether or not intentionally, the incitement of the proposed Robocop statue proves, albeit aided by the alternative economies provided by the Internet, how an idea can circumnavigate top-down public art commissioning. While it may be excessive to say that this is public art that comes from a public (often invisible or imagined whenever the term is evoked), it could be thought of as an unlikely proponent of an artistic intervention in an early stage of regeneration. Yet the image of Robocop is as absurdly profound as it gets, as it is also in itself a monument to regeneration.

Saim Demircan