The Museum of Nothing and Other Berlin Legends

2012,

Joanna Rajkowska's Swamptown. Sebastian Cichocki

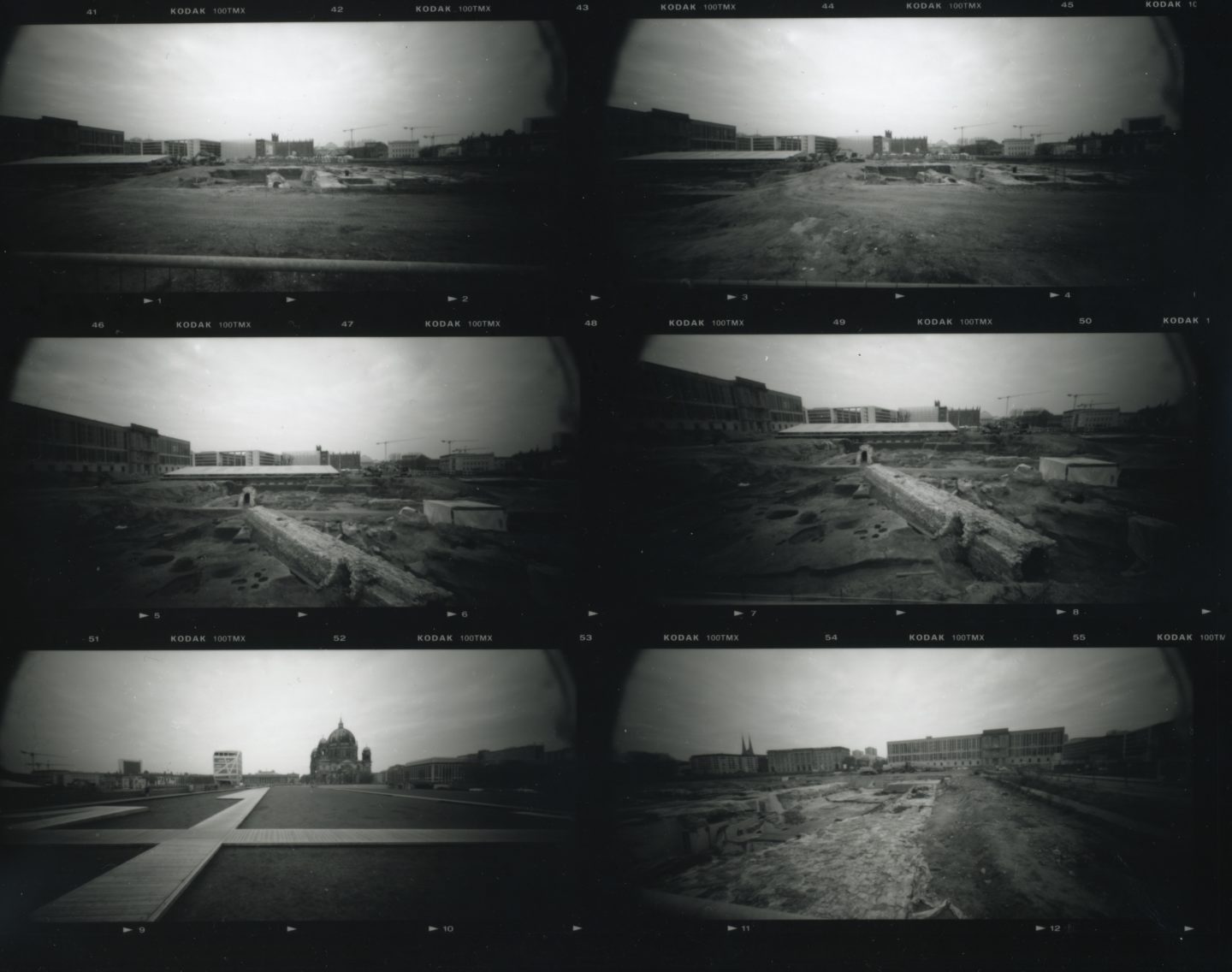

The Berliner Stadtschloss [Berlin City Palace], the seat of Prussian kings and German emperors, had survived a lot, including aerial bombings in 1945. Even though horribly mutilated in this last battle, the building could still have risen again. The authorities of the German Democratic Republic, however, handed down the final judgement, and in 1950 the Berliner Stadtschloss was raised to the ground. Another construction took its place, built in part from toxic asbestos: The Palace of the Republic, which was completed in 1976. The new palace had its time of splendour, and was, among other things, the seat of the GDR parliament. It was, however, condemned to a long slow death, having been transformed in 1990 into a living ruin, enlivened by an ever more vigorously growing constellation of weeds. This dying building nourished the imagination of artists who were intrigued by the image of the thousands of tons of concrete, steel and iron absurdly moored for almost twenty years in the very centre of the city. Trees growing on the roof of the Palace of the Republic were inventoried and saved by Ulrike Mohr – enriching the wild garden in Skulpturenpark. The building was also filmed by Tacita Dean, as well as Sophie Calle. One of the palace’s characteristic brown reflective glass windows was ‘transplanted’ by Cyprien Gaillard to an apartment block in Warsaw. The idea of the return of the Berliner Stadtschloss does not stir as much interest among artists as its socialist successor did. The idea of rebuilding the castle is treated as an identity aberration, an excess tinged with populism.

What does a return to old forms of architecture mean for the urban fabric, when employing discredited, or simply inappropriate, aesthetics? What denotes an architectural break with historical continuity? The idea of reconstructing an eighteenth century Prussian castle in the first decade of the twentieth century, more than six decades after its demolition, is not (as opponents contend) a sign of insanity marked by national hubris. It is rather a syndrome of the sadness eating away at Berlin – a sadness that cannot be erased with the help of well planned urban masquerades or cultural-research ‘procedures’. This sadness festers, like an improperly healed wound. It is inherited, not acquired, which only makes it that much more difficult to snuff out. It is not known when exactly the next phase of grief will come, stifling the city’s residents. A therapy based on anachronistic architectural decorations is risky. What spirits would the citizens of Berlin like to call forth, which demons to exorcise?

Swamptown – the phantasmagoric proposal by Polish artist Joanna Rajkowska of the raising (though in this case it might be better to use the verb ‘lowering’) of a monument, which would not in fact add new objects to the existing urban body, but rather remove unnecessary elements. In contrast to lasting monumental forms, this proposal is an open ‘interactive’ form, changing over time. A swamp instead of a Prussian castle is a ‘monument to nothing’, that is a double negation – a negation of a history which stifles us, and at the same time a negation of the mechanisms of amnesia which falsely frees us. Swamptown is the latest of Rajkowska’s ‘impossible monuments’, which grapples with the issues of amnesia, language and rituals of memory, as well as the physicality of the city, its growth and erosion. In the past she had proposed the following projects: anchoring a replica of the Hindenburg above Curitiba, Brazil (Two Days to Europe, 2011); boring a deep hole in the centre of Warsaw to reveal geological layers (Ravine, 2009); constructing a volcano-hearth in the Swedish city of Umeå (Umeå Volcano, 2006); as well as hanging an urn in the shape of a bat from a bridge in Bern, Switzerland (The Bat, 2009).

The impossible and paradoxical are functional, active elements in Rajkowska’s work – even when a project is not carried out. The dehistoricisation of Schlossplatz (which would be in this case be synonymous with an admission of guilt, as well as a will to begin everything anew – a ‘resetting’ of history) could take place through a return to basic organic forms which do not carry traces of an urban order forced by modern forms of organizing the city. Reducing the cityscape to mud is a calling to capitulate before historical memory, and at the same time is an abandonment of the obligatory antiseptic logic of contemporary cities. It is returning territory to non-human forces.

How long would it take for nature to reclaim the centre of Berlin if it were completely depopulated? Most likely in the first few months ubiquitous vegetation would appear (growing up out of each crack in the pavement, abandoned balconies, on mouldy rugs and carpets, and rotting libraries), treating flats, stairwells and railway stations like greenhouses. Unheated buildings would easily succumb to dampness. Crumbling walls and piles of discarded trash would become prey for microorganisms, fungi and lichens. Any fire not extinguished would overtake entire city districts, accelerating the process of its decomposition. Its underground infrastructure would survive the longest: metro tunnels, basements, warehouses and sewer pipes. But over time they, too, would be consumed – but not before they had become places to hibernate in for amphibians, reptiles, small mammals, and maybe larger predators which would more boldly venture into the newly reclaimed environment. We can observe these natural and inexorable processes in cities like in the centre of Detroit, areas around Chernobyl, as well as in the safety zone surrounding the nuclear power plant in Fukushima.

Joanna Rajkowska’s proposal is a radical fantasy, while at the same time a very concrete postulate. Should we not strive for true radicalism in our pursuit of historical forms, the weakness for urban scenery evoking some moment of historical elation (regardless of their authenticity – Krakow tours following in the footsteps of the movie Schindler’s List are examples of escapades to fictionalized history that become tangible)? If the centuries old Prussian castle is to be rebuilt (like the reconstructed districts of bombed out Warsaw), while at the same time attempting to regenerate populations of animals and plants that have been wiped out in some areas (for example, the European resident of marshy pools – the European pond turtle), why not return to a prehistoric landscape? And maybe to 2000 years B.C.? And why not a landscape from the time of the first Germanic settlements?

Berlin’s boggy past is even written into its name. Some hear the old Slavic berl, that is mud, which was supposed to refer to the city’s location on marshlands surrounding the Spree. Swamptown would therefore be a respite for memory, which itself was bogged down in the slime. Rajkowska spins an escape plan, purification and penance by a return to nature in its demonic and rawest form. Small flames would certainty rise up above the swamp, misleading lost travellers. In Slavic mythology treacherous demons would use small lights at night above swamps in order to lead unfortunate men to certain death, sucked under by the murderous mud. They were (of course!) souls of those who were evil or cruel towards their brethren, and they roamed the swamps in the form of lost lights, with no hope of salvation. Without its enormous gloomy castle sunk in the mud, Schlossplatz becomes a museum of emptiness, the inverse (yet at the same time a natural stage of its evolution) of a mausoleum, filled with petrified objects. This leads us to – and not for the first time when attempting to describe Rajkowska’s impossible monuments – the early writings of Robert Smithson. The categories of site and non-site, displacement and entropy are extremely useful, just like the concept of nonfeasance (or non-action) – the abdication of rights to the powers of nature, which modify a work, leading to its (de)materialisation. The artist plays the role of researcher-enthusiast, casting off the role of the creator of objects decorating the city (the sanctioned role of the artist in public space), tracking down and looking for material proof: cracks and paradoxes, both intellectual and material. The city itself becomes a museum.

In his 1968 essay ‘Some Void Thoughts on Museums’, Robert Smithson underscored that history is only a collection of ‘facsimiles of events’ held together as a whole only with the help of the cement of fragmentary biographical information and facts chosen by capricious researchers (be it the demolition of a building, a duel, the taking of a city, a bombing, the first signs of mental illness, etc.). These are, however, only ruins of the past, quotes and fragments, difficult to shape into a convincing coherent narrative. Of course the extreme example, most prone to manipulation, is the history of art and architecture. The history of buildings and objects settles and therefore slowly takes the shape of the next tectonic layers – easy to appropriate, correct, and add footnotes to. Smithson writes that ‘[v]isiting a museum is a matter of going from void to void. Hallways lead the viewer to things once called “pictures” and “statues”. Anachronisms hang and protrude from every angle’. He observed and commented that ‘[m]useums are tombs, and it looks like everything is turning into a museum’.

The Berlin palace is therefore a tomb, for aspirations, disappointments, offences, betrayals, ambitions, as well as dreams about power and order – a grave written in architecture. Swamptown, or perhaps also swamp museum (assuming that the whole world becomes a museum), which Joanna Rajkowska proposes has the potential of continual growth, absorbing other neighbourhoods, motorways, viaducts and entire suburbs. It is a work which will consume the entire world. It encourages the celebration of emptiness – of a kind of void whose reception is not disturbed by any petrified remains, be they human or architectural. This monument is irreversible, though it is constantly undergoing changes, mutating. History ends and the growth of organic matter begins. At the same time rot, decay, entropy – processes which free us from the weight of history (perhaps to our own misfortune), are more effective than embalming and erecting mausoleums.