And In the Wilderness

28.09 - 25.11.2023 // 16.02 – 17.03.2024,

group exhibition

BWA Warszawa Gallery, Warszawa, Poland // Krupa Foundation, Wrocław, Poland

What does the 1910 adventure novel In Desert and Wilderness by Henryk Sienkiewicz have to do with the wilderness on the border with Belarus in 2023? Polish children’s youthful reading has lost its innocence, just as the idea of humanism has turned out to be an illusion. Maciej Gdula wrote that In Desert and Wilderness is a novel that “promotes a sense of superiority over the people of other races, shows how to celebrate one’s own culture at the same time disregarding the Other and alien cultures, and justifies the domination of the strong over the weak. […] Teaching contempt for the dominated Other, who is supposedly lower in the hierarchy, is the worst possible cultural poison. Once ingested, liberation or freedom is understood as the freedom to rule over others. We have plenty of that in Poland.” Meanwhile, Sienkiewicz’s canon continues to shape successive generations.

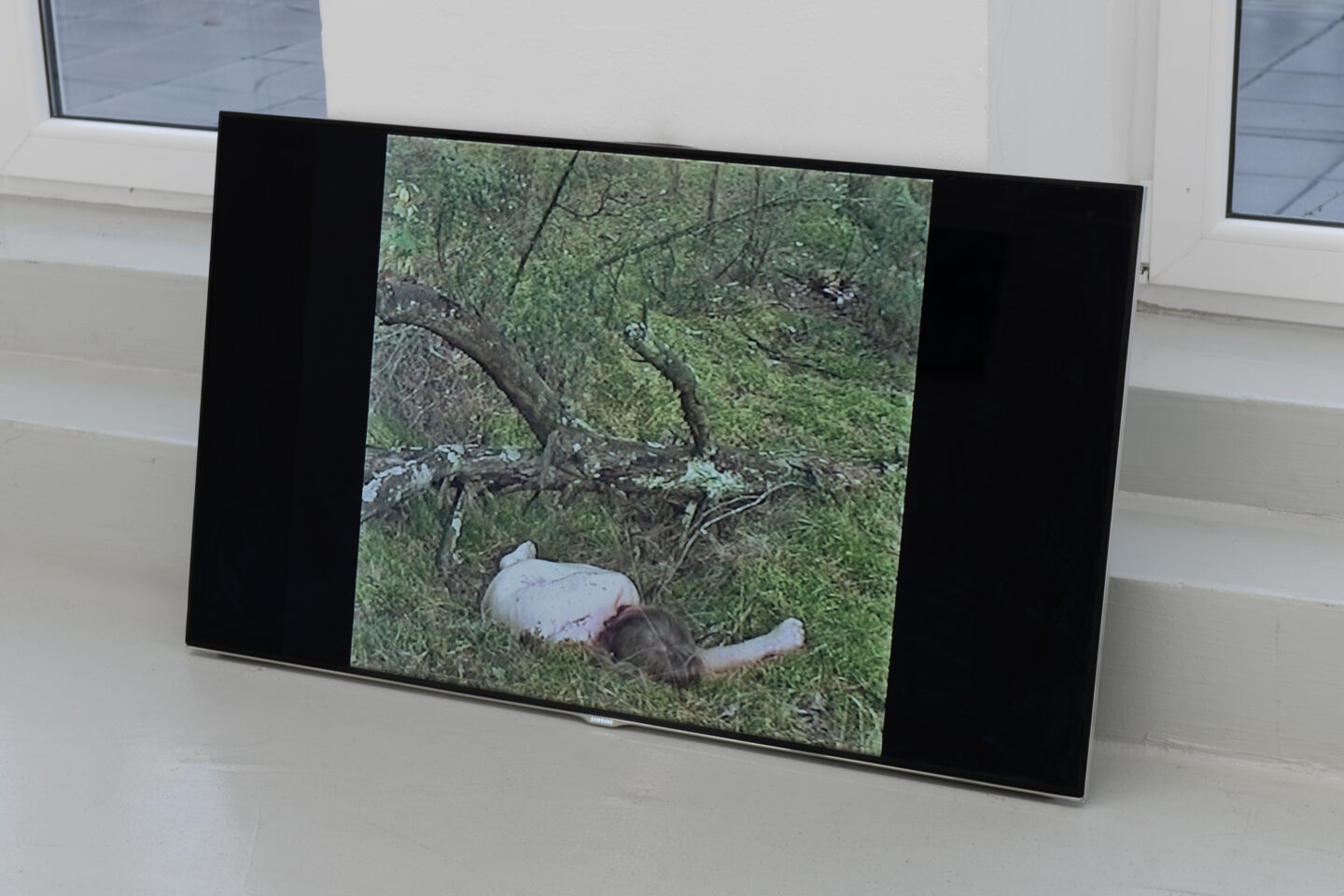

Mahlet, a young Ethiopian woman, is one of many refugees who died alone in the wilderness of the Białowieża Forest. Letting this happen is inhuman, heartrending and raises questions about what humanity is. Fear of death at the hands of her compatriots drives a young Syrian mother to leave everything (nothing) behind and set off for Libya, risking the lives of her own children by boarding an overcrowded boat in the hope of reaching Italy. The prospect of lifetime military service forces a teenage boy from Eritrea to cross the deadly Sahara, dreaming of living in a free world that he does not know. Hope(lessness) drives young people to embark on a dramatic journey with smugglers from Khartoum to North Africa, fully aware that many perish in the desert and never reach their destination. Rafał Bujnowski’s small, almost abstract pyrographs were made near the Spanish coast, where migrants from Africa arrive.

Wilhelm Sasnal’s two paintings complement each other, reinforcing the atmosphere of fear and hopelessness. The same series includes a landscape (not shown in the exhibition) with Kaczyński and Błaszczak – people “unworthy of painting,” according to the artist. Similarly, Joanna Rajkowska uses the term “anti-monument” when referring to her sculpture SORRY.

We present works created in response to current events, but also prophetic pieces from a few or more years ago, such as those by Aleka Polis and Agnieszka Kalinowska. The latter used the iconography of a road sign in a work made over a decade ago. The so-called immigration sign, depicting a man, woman, and girl with pigtails running, warned motorists on the interstate highway on the border between Mexico and the United States to avoid immigrants darting across the road. The signs were installed in response to more than a hundred traffic strike fatalities between 1987 and 1990. However, instead of a sense of safety and public order, they created an impression of panic, chaos, and the breakdown of social norms.

In 2003, Aleka Polis created a performance in which she personally explored the experience of hypothermia. Years later, she dedicated it to “migrants and people who help them, and all those who love their neighbor as themselves.”

Gizela Mickiewicz, working on her sculpture Paths of Boredom and Stress, referred to situations when anxiety or stress are mixed with boredom caused by waiting to see how important things will turn out. As the artist explains, “For example, when you are sitting in a hospital room waiting to receive important information, you may have a very vivid sense of time dragging on, but at the same time you feel a growing anxiety. What I find interesting in such situations is the urge to move around, to give vent to stress. Such movement is a semblance of action, of not being passive in a situation over which you really have no control. You can see such a choreography of anxiety in hospitals – people walking in circles along a small section of the corridor. What I find interesting is this kind of liminal situation where the paths of boredom and stress intersect. When I apply this state to a situation of hiding – tension and anxiety mixed with too much time without meaningful activity – it seems close to me.”

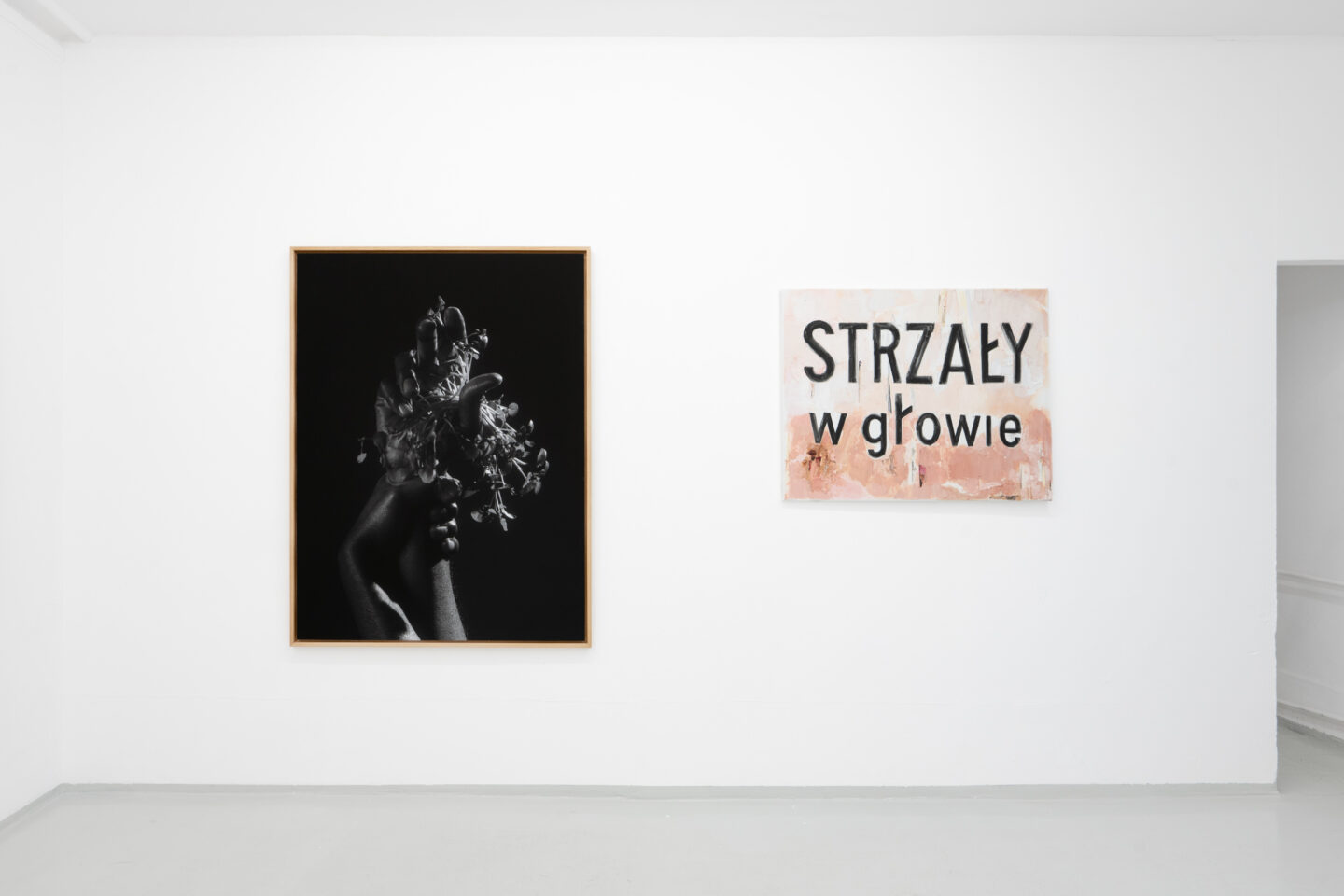

Witek Orski’s photograph Wet Plants is part of the project What Is Beautiful I Don’t Know Anymore, dedicated to melancholy. H., a refugee from Sudan who arrived in Poland through the eastern border after a harrowing crossing, is holding watercress in his hand. In the 14th century, according to the so-called humoral theory, it was believed to be one of the plants that could cure melancholy and depression. To this day, H. struggles with the psychological consequences of the deep trauma of his journey to Europe.

Lament by Karolina Freino consists of a light box and the cry of the Mount Cameroon spurfowl (Pternistis camerunensis), an endangered endemic bird of the Mongo ma Ndemi in the Cameroon Mountains. A mourning song composed from its voice was played in the Polish-Belarusian border area, in the village of Ozierany, on the border river Svislach. On 16 February 2023, the body of Livine Solange Njengoue Nguekam from Cameroon was found nearby, floating in the Svislach. Following her family’s wishes, she was buried in a cemetery in nearby Krynki. Livine is one of more than 50 victims of the humanitarian crisis that has been ongoing on the Polish-Belarusian border since 2021. More than three hundred people are listed as missing.

The film by Szymon Ruczyński, a student at the Film School in Łódź, is based on his own experiences as a resident of Bialowieża. As he said in an interview with Dwutygodnik, “I still have some of these objects I found [in the forest], I don’t know how to throw them away. A child’s glove, a cap… When I’m supposed to go somewhere and talk about what’s happening in our area, I take them with me. […] It’s important for me to be able to touch them, to give them to another person and say: this really happened. This is tangible proof that I’m not making it up. If you don’t have anything to do with the situation, you start telling yourself that it’s not so bad there, and your brain runs away to the comforts of life. I think that’s why it doesn’t resonate so much in Poland, because it’s so hard to understand. I have to remind myself about it all the time. If you’re not there all the time, it’s easy to get swallowed up by everyday life, as if nothing was happening.”

This tangible evidence that the forest is no longer the same can also be seen in Karolina Jabłońska’s painting. The cold space of the forest contains seemingly inconspicuous objects – a shoe, a glove. But for those who have had the opportunity to be in the Białowieża Forest, to enter the borderland, this experience of finding strange objects is real. A shoe, a telephone, a backpack. This is not the forest we remember from Adam Wajrak’s stories about wolves or Włodzimierz Puchalski’s photographs. There is less and less of that romantic atmosphere. The couple tangled in barbed wire in Katarzyna Przezwańska’s work can be seen as a metaphor for people’s drama in the forest. All the romance is gone. As we look at the refugee crisis, the armed conflicts in Ukraine, in Gaza, in Africa, our hope that we are wise and capable of keeping the peace vanishes. The symbolism of the dove of peace from Filip Rybkowski’s work is no longer relevant, it is turning into an illusion of a safe world that is creaking, flaking and disintegrating before our eyes. What this means is that more and more people will be looking for a better place to live.

The exhibition ends with a film documentary by Piotr Czaban, a journalist who has been observing the crisis at the border from the very beginning.

Human drama is constantly happening in the wilderness. We want this exhibition to open our heads and hearts to the plight of refugees and migrants. We want to ask questions about freedom, the need for agency, responsibility and indifference.