Palestinian Blog

2008,

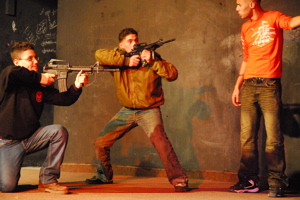

29 March - 15 May 2008, Freedom Theatre

Jenin, West Bank

29 March – 15 May 2008, Freedom Theatre, Jenin, West Bank

___________________________________________________________________________

18 May 2008

That day, Yehuda Shaul couldn’t take us to Hebron. We were a threat to public safety. The settlers might attack us, which is why it was us, not them, that were a hazard. Yehuda decided to take the bus south of Hebron, towards Susya.  We drove down some very winding roads. First we stopped near a place that Yehuda calls Lucifer Outpost. A guy lives there who, when the apartheid had ended in south Africa, moved here. He’s converted to Judaism. Now his jeep stood in front of us. The guy got worried, reached for his mobile. Within a few minutes an Israeli police patrol appeared and it never left us again. We then went to a tiny Palestinian village – Susya, or rather what’s left of it. A couple of families, already resettled many times (the soldiers come in the night, load everyone on trucks and drive them kilometres away), live here in tents stitched together with pieces of tarpaulin, rags, blankets and plastic bags. They have their leader, Nasser, a small, lively man in a woollen cap.

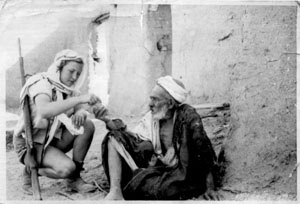

We drove down some very winding roads. First we stopped near a place that Yehuda calls Lucifer Outpost. A guy lives there who, when the apartheid had ended in south Africa, moved here. He’s converted to Judaism. Now his jeep stood in front of us. The guy got worried, reached for his mobile. Within a few minutes an Israeli police patrol appeared and it never left us again. We then went to a tiny Palestinian village – Susya, or rather what’s left of it. A couple of families, already resettled many times (the soldiers come in the night, load everyone on trucks and drive them kilometres away), live here in tents stitched together with pieces of tarpaulin, rags, blankets and plastic bags. They have their leader, Nasser, a small, lively man in a woollen cap.  Susya is an important place. It is surrounded by a chain of Israeli settlements – Maon, Yatir, and others – and outposts. An outpost is a place surrounded by a barbed-wire fence, often with a watchtower. The military stations there. With time, the outpost develops an outer layer of trailers and turns into a settlement. This is illegal under international law. Susya is the last Palestinian village that has survived here. The resettled families have always returned. The fight for Susya is not only a fight for territory, it is also a fight, probably already lost, for the preservation of the culture of the local cave dwellers. Their culture was first described by 19th-century anthropologists. They drilled caves, inhabited them, found sources of potable water, bred cattle. But then the Israelis came with bulldozers and filled the cave entrances in with rubble. That’s how the 170-year-old culture of the cave dwellers came to an end.

Susya is an important place. It is surrounded by a chain of Israeli settlements – Maon, Yatir, and others – and outposts. An outpost is a place surrounded by a barbed-wire fence, often with a watchtower. The military stations there. With time, the outpost develops an outer layer of trailers and turns into a settlement. This is illegal under international law. Susya is the last Palestinian village that has survived here. The resettled families have always returned. The fight for Susya is not only a fight for territory, it is also a fight, probably already lost, for the preservation of the culture of the local cave dwellers. Their culture was first described by 19th-century anthropologists. They drilled caves, inhabited them, found sources of potable water, bred cattle. But then the Israelis came with bulldozers and filled the cave entrances in with rubble. That’s how the 170-year-old culture of the cave dwellers came to an end.  Eighty percent of water sources are controlled by the settlers. Of the two sources available to the people of Susya, one has been contaminated by the settlers, who rolled a car into it, and is good only for cattle. People have been left without enough water. The only thing they can do is go to the settlers, buy 2 cubic metres of potable water from them for 300 shekels and haul it back to the village on a donkey’s back. This year the village was saved by European activists, who brought in water for the whole, exceptionally dry, summer. Nasser showed us olive trees felled by the settlers. We came up close to see the stumps and then two figures of armed soldiers appeared on the hilltop. The people of Susya have no access to most of their fields. Illegal fences built by the settlers and the army effectively prevent them from reaching their arable land. Under an old law, dating back to Ottoman times, if someone fails to farm his land for three years in a row, they lose their right to it. The settlers are an incarnation of evil for the Israeli soldier. One, of course, who feels personally responsible in any way for what he does. When you read soldiers’ testimonies contained in the three-volume book Breaking the Silence, it turns out that the victims here are both the Palestinians, spat at, detained, ‘dried’, tortured and deprived of means of earning their living, as well as the soldiers, with their moral doubts and sense of shame and guilt. In fact, there are others who are worse than us, the soldiers say, look at the Border Police guys. If you tell a Palestinian he’ll be handed over to the Border Police, he will do whatever you want, will humiliate himself, start begging you on his knees for you not to do it. There is also the bad superior, and bad procedures, such as the ‘neighbour’ procedure, where soldiers use local civilians, who often die in the process, as cover when searching terrorist suspects’ homes. The procedure used to be called something else, but it was banned by the Israeli High Court, so its name was changed – the procedure remains the same. There are also other bad practices, such as the ‘feeling the presence’ procedure where Israeli soldiers do everything to disturb the peace of say, a night’s sleep, at a given neighbourhood. How? However. There are no rules, or rather the rules are defined by the officer in charge. Depending on his personality, he can order you to search a house in the middle of the night, or shoot in the air, or shoot at house walls… The point is for the Palestinians to be aware at all times that the army is near. Another evil is using children as human shields. In many situations. Reported to be highly effective.

Eighty percent of water sources are controlled by the settlers. Of the two sources available to the people of Susya, one has been contaminated by the settlers, who rolled a car into it, and is good only for cattle. People have been left without enough water. The only thing they can do is go to the settlers, buy 2 cubic metres of potable water from them for 300 shekels and haul it back to the village on a donkey’s back. This year the village was saved by European activists, who brought in water for the whole, exceptionally dry, summer. Nasser showed us olive trees felled by the settlers. We came up close to see the stumps and then two figures of armed soldiers appeared on the hilltop. The people of Susya have no access to most of their fields. Illegal fences built by the settlers and the army effectively prevent them from reaching their arable land. Under an old law, dating back to Ottoman times, if someone fails to farm his land for three years in a row, they lose their right to it. The settlers are an incarnation of evil for the Israeli soldier. One, of course, who feels personally responsible in any way for what he does. When you read soldiers’ testimonies contained in the three-volume book Breaking the Silence, it turns out that the victims here are both the Palestinians, spat at, detained, ‘dried’, tortured and deprived of means of earning their living, as well as the soldiers, with their moral doubts and sense of shame and guilt. In fact, there are others who are worse than us, the soldiers say, look at the Border Police guys. If you tell a Palestinian he’ll be handed over to the Border Police, he will do whatever you want, will humiliate himself, start begging you on his knees for you not to do it. There is also the bad superior, and bad procedures, such as the ‘neighbour’ procedure, where soldiers use local civilians, who often die in the process, as cover when searching terrorist suspects’ homes. The procedure used to be called something else, but it was banned by the Israeli High Court, so its name was changed – the procedure remains the same. There are also other bad practices, such as the ‘feeling the presence’ procedure where Israeli soldiers do everything to disturb the peace of say, a night’s sleep, at a given neighbourhood. How? However. There are no rules, or rather the rules are defined by the officer in charge. Depending on his personality, he can order you to search a house in the middle of the night, or shoot in the air, or shoot at house walls… The point is for the Palestinians to be aware at all times that the army is near. Another evil is using children as human shields. In many situations. Reported to be highly effective.  Evil is abstract, delegated onto others, you as you are always in between. You are a neutral, feeling individual, with your dilemmas, your doubts, your disgust. When I look at visitors from Europe treating the state of Israel, evil embodied in a state abstraction, with similar disgust, I start to have doubts. I remember a German filmmaker in Jenin waiting for weeks for his main character, Ahmad, to appear. He said he didn’t understand why Ahmad wasn’t turning up – after all, he was here to help the Palestinian cause! I looked at him, just as I looked at myself, and I thought that it is we ourselves who are responsible for what has happened, and is still happening, in Israel. That it’s great that we want to help – but whom are we really helping? That Israel is our project, after all, an effect of Europe’s colonial ambitions and a conviction that our way of living is better than anyone else’s. That living in a sloping-roof house is better than living in a rock cave.

Evil is abstract, delegated onto others, you as you are always in between. You are a neutral, feeling individual, with your dilemmas, your doubts, your disgust. When I look at visitors from Europe treating the state of Israel, evil embodied in a state abstraction, with similar disgust, I start to have doubts. I remember a German filmmaker in Jenin waiting for weeks for his main character, Ahmad, to appear. He said he didn’t understand why Ahmad wasn’t turning up – after all, he was here to help the Palestinian cause! I looked at him, just as I looked at myself, and I thought that it is we ourselves who are responsible for what has happened, and is still happening, in Israel. That it’s great that we want to help – but whom are we really helping? That Israel is our project, after all, an effect of Europe’s colonial ambitions and a conviction that our way of living is better than anyone else’s. That living in a sloping-roof house is better than living in a rock cave.  It is us, in Poland, in Germany, who got rid of Jews. A policy of extermination, conducted in a more or less radical manner, is something we know perfectly well. Amos Oz: why has Israel not developed into the world’s most egalitarian and creative social democracy? I’d say that one of the main reasons was the mass immigration of Holocaust survivors, Middle Eastern Jews, and non-socialistic or anti-socialistic Zionists desiring ‘normalisation’. The Holocaust had convinced many Jews that the cruel game of the nations has to played according to its cruel laws: statehood, military establishment, and a pessimistic conception of the use of military force. At the same time, some of them wanted Israel to become a replica of the pre-war bourgeois Central Europe, with its red tile roofs and good manners, with Frau Direktor and Herr Doktor, Gemütlichkeit and Bavarian cream – Franz Joseph Vienna transplanted to the Holy Land. 13 May 2008 This is the last part of my trip. Outside the window of my small room bangers are exploding. It could seem that grownups are playing like children, but it’s simply the only thing they can do to celebrate a sad occasion: today is the sixtieth anniversary of the Nakba, the Palestinian catastrophe of 1948. The crowd by the Damascene Gate sways. There are a lot of soldiers and police around. When whistling and applause starts, the soldiers climb on one another’s backs and grab their M16s.

It is us, in Poland, in Germany, who got rid of Jews. A policy of extermination, conducted in a more or less radical manner, is something we know perfectly well. Amos Oz: why has Israel not developed into the world’s most egalitarian and creative social democracy? I’d say that one of the main reasons was the mass immigration of Holocaust survivors, Middle Eastern Jews, and non-socialistic or anti-socialistic Zionists desiring ‘normalisation’. The Holocaust had convinced many Jews that the cruel game of the nations has to played according to its cruel laws: statehood, military establishment, and a pessimistic conception of the use of military force. At the same time, some of them wanted Israel to become a replica of the pre-war bourgeois Central Europe, with its red tile roofs and good manners, with Frau Direktor and Herr Doktor, Gemütlichkeit and Bavarian cream – Franz Joseph Vienna transplanted to the Holy Land. 13 May 2008 This is the last part of my trip. Outside the window of my small room bangers are exploding. It could seem that grownups are playing like children, but it’s simply the only thing they can do to celebrate a sad occasion: today is the sixtieth anniversary of the Nakba, the Palestinian catastrophe of 1948. The crowd by the Damascene Gate sways. There are a lot of soldiers and police around. When whistling and applause starts, the soldiers climb on one another’s backs and grab their M16s.  Three years after the end of WWII, the Zionists resettled 700,000 people to refugee camps, which with time became almost a model of the contemporary ghetto. The colonisation of Palestine has been carried out to this day in keeping with the well-tried methods of the apartheid. There is no right of return for the resettled Palestinians. When they hear the words ‘right to return’, even the most left-leaning Israelis react with a hard no. In fact, as I have realised after nearly two months in Israel, here ‘left-leaning’ means simply ‘not far right’, ‘not ultra-nationalist’. Soldiers in Hebron scorn other soldiers who do not participate eagerly in cruel practices against the Palestinians and call them ‘leftie-softie’. I have the impression that sixty years later the tragedy of the Nakba remains as strongly felt on both sides of the barricade. I’m not trying to make an equation between the victims and the perpetrators. Tragedies destroy both sides. And loud celebrations that effectively eliminate the Palestinian issue from the narrative won’t help here. It is enough to walk around some Israeli town, best a small one like Holon (I recently got lost there and got to know many strange streets), or to go any town on the West Bank… It is something that is present in the gestures, in the gazes. On the one hand, desperation, despair, chaos, being used to humiliation, demoralisation, simply decay – all that is present in Palestine, in the way these people walk, talk, fear, laugh.

Three years after the end of WWII, the Zionists resettled 700,000 people to refugee camps, which with time became almost a model of the contemporary ghetto. The colonisation of Palestine has been carried out to this day in keeping with the well-tried methods of the apartheid. There is no right of return for the resettled Palestinians. When they hear the words ‘right to return’, even the most left-leaning Israelis react with a hard no. In fact, as I have realised after nearly two months in Israel, here ‘left-leaning’ means simply ‘not far right’, ‘not ultra-nationalist’. Soldiers in Hebron scorn other soldiers who do not participate eagerly in cruel practices against the Palestinians and call them ‘leftie-softie’. I have the impression that sixty years later the tragedy of the Nakba remains as strongly felt on both sides of the barricade. I’m not trying to make an equation between the victims and the perpetrators. Tragedies destroy both sides. And loud celebrations that effectively eliminate the Palestinian issue from the narrative won’t help here. It is enough to walk around some Israeli town, best a small one like Holon (I recently got lost there and got to know many strange streets), or to go any town on the West Bank… It is something that is present in the gestures, in the gazes. On the one hand, desperation, despair, chaos, being used to humiliation, demoralisation, simply decay – all that is present in Palestine, in the way these people walk, talk, fear, laugh.  In the gestures, in the way the Israelis talk and look, there is right and grievance, both cemented by trauma. Their own, of course. If you want to understand anything here, you must not ignore this – comprehension-eluding, paradoxically – but important element – body language. *** ‘It’s just so that a higher culture squeezes out a lower one. Take Rome for example…’ (from a conversation with an elderly Israeli lady) *** ‘I don’t want to feel guilty for what is happening in the West Bank. Why should I feel guilty? I don’t want to feel guilty.’ (from a conversation with a young Israeli woman) *** From interviews with soldiers serving in Hebron featured in the book Breaking the Silence. Soldiers Speak Out About Their Service in Hebron: *** ‘Now no one can say we don’t take care of these animals.” Paramedic Referring to a 12-year old run over by a vehicle of the Jewish settlement… and taking it to the ambulance. ***

In the gestures, in the way the Israelis talk and look, there is right and grievance, both cemented by trauma. Their own, of course. If you want to understand anything here, you must not ignore this – comprehension-eluding, paradoxically – but important element – body language. *** ‘It’s just so that a higher culture squeezes out a lower one. Take Rome for example…’ (from a conversation with an elderly Israeli lady) *** ‘I don’t want to feel guilty for what is happening in the West Bank. Why should I feel guilty? I don’t want to feel guilty.’ (from a conversation with a young Israeli woman) *** From interviews with soldiers serving in Hebron featured in the book Breaking the Silence. Soldiers Speak Out About Their Service in Hebron: *** ‘Now no one can say we don’t take care of these animals.” Paramedic Referring to a 12-year old run over by a vehicle of the Jewish settlement… and taking it to the ambulance. ***  The great thing about Hebron, the thing that gets to you more than anything else, is the total indifference it instills in you. It’s hard to describe the kind of enormous sea of indifference you’re swimming in while you’re there. It’s possible to explain a little, through little anecdotes, but it’s not enough to make it really clear. One story is about a little kid, a boy of about six, who passed by me at my post. We were at… He said to me: “Soldier, listen, don’t get annoyed, don’t try and stop me, I’m going out to kill some Arabs.” I look at the kid and don’t quite understand exactly what I’m supposed to do. So he says: “First, I’m going to buy a popsicle at Gotnik’s”—that’s their grocery store, “then I’m going to kill some Arabs.” I had nothing to say to him. Nothing. I went completely blank. And that’s not such a simple thing… that a city, that such an experience can turn someone who was an educator, a counselor, who believed in education, who believed in talking to people, even if their opinions were different. But I had nothing to say to a kid like that. There’s nothing to say to him. *** In one of our conversations with the Border Police in Hebron, two of them were bragging about how much they liked to take a Palestinian whom they caught throwing stones or just throwing a word at them, or looking at them the wrong way. They’d put him into an armored jeep and then hit him with the spark-mufflers of their weapons in the chest or the stomach or the neck. Then they’d bet how fast they could take the turn in the road where they’d throw him out of the armored jeep. If you ask me, then yes, it really bothered me, but what could I do about it? Q: You know that the Border Police did this to someone afterwards and he was killed. They murdered someone. That’s very sad. And, so? Q: Did you recognize any of the murderers, the guys who are standing trial now? No. I didn’t recognize anyone. I don’t know them. I just heard ‘em talking. ***

The great thing about Hebron, the thing that gets to you more than anything else, is the total indifference it instills in you. It’s hard to describe the kind of enormous sea of indifference you’re swimming in while you’re there. It’s possible to explain a little, through little anecdotes, but it’s not enough to make it really clear. One story is about a little kid, a boy of about six, who passed by me at my post. We were at… He said to me: “Soldier, listen, don’t get annoyed, don’t try and stop me, I’m going out to kill some Arabs.” I look at the kid and don’t quite understand exactly what I’m supposed to do. So he says: “First, I’m going to buy a popsicle at Gotnik’s”—that’s their grocery store, “then I’m going to kill some Arabs.” I had nothing to say to him. Nothing. I went completely blank. And that’s not such a simple thing… that a city, that such an experience can turn someone who was an educator, a counselor, who believed in education, who believed in talking to people, even if their opinions were different. But I had nothing to say to a kid like that. There’s nothing to say to him. *** In one of our conversations with the Border Police in Hebron, two of them were bragging about how much they liked to take a Palestinian whom they caught throwing stones or just throwing a word at them, or looking at them the wrong way. They’d put him into an armored jeep and then hit him with the spark-mufflers of their weapons in the chest or the stomach or the neck. Then they’d bet how fast they could take the turn in the road where they’d throw him out of the armored jeep. If you ask me, then yes, it really bothered me, but what could I do about it? Q: You know that the Border Police did this to someone afterwards and he was killed. They murdered someone. That’s very sad. And, so? Q: Did you recognize any of the murderers, the guys who are standing trial now? No. I didn’t recognize anyone. I don’t know them. I just heard ‘em talking. ***  I’d come home, then go back to Hebron and feel as though I’d gone abroad, really… as though in one go I simply cut to a totally different place. Whatever I used to call democracy here, would simply vanish in Hebron. Jews did as they pleased there, there were no laws. No traffic laws. Nothing. Whatever they do there is done in the name of religion, and anything goes – breaking into shops, that’s allowed… As a soldier I had a real problem because I come from a family that believes in values, in morals. I was in a youth movement. I knew about democracy, had learned about it in school. And I find myself in an army post, having to say to people: “Listen, you can’t get through here now.” “Why not?” “Because these are the orders now”… Simple. I didn’t really have any good reasons to give them, and it wouldn’t matter what I’d say, they were still prevented from moving on. Or entering someone’s house and having to say: “Okay, now I want all the children to go into one room, I want to search your home”. I think that if this happened the other way around, I don’t know what I’d do. Really. I’d go crazy if my home would be entered like that. I tried to imagine my parents, my family, what would they actually do if people with guns would enter a home with small children, 4-5 years old, point weapons at them and say: “Okay, everybody move!” I had a really hard time with this, with sitting at the post and telling people “You cannot pass”, or “Move on!” Or when we arrested people who had broken curfew. What does that mean, breaking the curfew? It just means they went out to do some shopping, breaking curfew. So the platoon commander would say: “Okay, now everyone move over to the side.” After making them stand on the side, he’d tell us to “dry them up for a couple of hours”. I said: “What do we do with them for hours?” “Just make them sit here.” *** I said, “Listen, what’s the deal, how long do you want to detain him for?” He said, “Listen, you can do whatever you want, whatever you feel like doing. If you feel there’s a problem with what he’s done, if you feel something’s wrong, even the slightest thing, you can detain him for as long as you want.” *** I was ashamed of myself the day I realized that I simply enjoy the feeling of power. I don’t believe in it: I think this is not the way to do anything to anyone, surely not to someone who has done nothing to you, but you can’t help but enjoy it. People do what you tell them. You know it’s because you carry a weapon. Knowing that if you didn’t have it, and if your fellow soldiers weren’t beside you, they would jump on you, beat the shit out of you, and stab you to death—you begin to enjoy it. Not merely enjoy it, you need it. *** Those were excerpts from the interviews collected in the three volumes of Breaking the Silence. You can find them here: http://www.shovrimshtika.org/publications_e.asp. And that’s it for today. It’s completely dark outside. 10 May 2008 Two days under the sign of Hebron.

I’d come home, then go back to Hebron and feel as though I’d gone abroad, really… as though in one go I simply cut to a totally different place. Whatever I used to call democracy here, would simply vanish in Hebron. Jews did as they pleased there, there were no laws. No traffic laws. Nothing. Whatever they do there is done in the name of religion, and anything goes – breaking into shops, that’s allowed… As a soldier I had a real problem because I come from a family that believes in values, in morals. I was in a youth movement. I knew about democracy, had learned about it in school. And I find myself in an army post, having to say to people: “Listen, you can’t get through here now.” “Why not?” “Because these are the orders now”… Simple. I didn’t really have any good reasons to give them, and it wouldn’t matter what I’d say, they were still prevented from moving on. Or entering someone’s house and having to say: “Okay, now I want all the children to go into one room, I want to search your home”. I think that if this happened the other way around, I don’t know what I’d do. Really. I’d go crazy if my home would be entered like that. I tried to imagine my parents, my family, what would they actually do if people with guns would enter a home with small children, 4-5 years old, point weapons at them and say: “Okay, everybody move!” I had a really hard time with this, with sitting at the post and telling people “You cannot pass”, or “Move on!” Or when we arrested people who had broken curfew. What does that mean, breaking the curfew? It just means they went out to do some shopping, breaking curfew. So the platoon commander would say: “Okay, now everyone move over to the side.” After making them stand on the side, he’d tell us to “dry them up for a couple of hours”. I said: “What do we do with them for hours?” “Just make them sit here.” *** I said, “Listen, what’s the deal, how long do you want to detain him for?” He said, “Listen, you can do whatever you want, whatever you feel like doing. If you feel there’s a problem with what he’s done, if you feel something’s wrong, even the slightest thing, you can detain him for as long as you want.” *** I was ashamed of myself the day I realized that I simply enjoy the feeling of power. I don’t believe in it: I think this is not the way to do anything to anyone, surely not to someone who has done nothing to you, but you can’t help but enjoy it. People do what you tell them. You know it’s because you carry a weapon. Knowing that if you didn’t have it, and if your fellow soldiers weren’t beside you, they would jump on you, beat the shit out of you, and stab you to death—you begin to enjoy it. Not merely enjoy it, you need it. *** Those were excerpts from the interviews collected in the three volumes of Breaking the Silence. You can find them here: http://www.shovrimshtika.org/publications_e.asp. And that’s it for today. It’s completely dark outside. 10 May 2008 Two days under the sign of Hebron.  I had just come back, very tired, I don’t know why. I lay on my bed, covered myself with a colourful blanket, and for two hours listened to music, almost dozing off. Music from here. I seldom do it. I can’t live without sounds here. Jenin, Tulkarem, Ramallah, Hebron, Susya, Yatta, Bethlehem, Aroup, everything is a sequence of sounds here: shouts, car horns, conversations, the West Bank is very noisy. I cooked two corn cobs for dinner and sat in the hostel’s tea/coffee room. A guy sat down next to me who works here, a Jordanian who spent his life in California. I asked him why he came back. Divorce, nervous breakdown, conversion, Jesus Christ. There is something very beautiful about this man, a right kind of calmness, almost deadly. His eyes are always half closed. He said that when he was been trying to overcome his depression, he read. The Bible, all kinds of books. He read without a break, eight hours a day. He reads here too. He sits in an armchair, at the top of the stairs, right above the greengrocery in the gate, amid the strong scent of peppermint, apples, aubergines, and cucumbers. And he reads. It seems to me I regularly see at least two Jews waiting all day for the Messiah to appear, near the Old Town gates.

I had just come back, very tired, I don’t know why. I lay on my bed, covered myself with a colourful blanket, and for two hours listened to music, almost dozing off. Music from here. I seldom do it. I can’t live without sounds here. Jenin, Tulkarem, Ramallah, Hebron, Susya, Yatta, Bethlehem, Aroup, everything is a sequence of sounds here: shouts, car horns, conversations, the West Bank is very noisy. I cooked two corn cobs for dinner and sat in the hostel’s tea/coffee room. A guy sat down next to me who works here, a Jordanian who spent his life in California. I asked him why he came back. Divorce, nervous breakdown, conversion, Jesus Christ. There is something very beautiful about this man, a right kind of calmness, almost deadly. His eyes are always half closed. He said that when he was been trying to overcome his depression, he read. The Bible, all kinds of books. He read without a break, eight hours a day. He reads here too. He sits in an armchair, at the top of the stairs, right above the greengrocery in the gate, amid the strong scent of peppermint, apples, aubergines, and cucumbers. And he reads. It seems to me I regularly see at least two Jews waiting all day for the Messiah to appear, near the Old Town gates.  A soldier in Hebron came up to me today and asked, ‘What’s your religion?’ Hebron began very early in the morning today. At 8.30 a.m. I stood across the street from Jerusalem’s Central Bus Station, waiting for a bus with a group of Canadians, Britons, a gay couple from Sweden, and a very elderly couple from Israel. They were so moving I couldn’t tear my eyes off them. Very elderly, around eighty, beautiful, when they said something to me, the gentleman always asked, ‘Deutsch or English?’ He would then forget my reply, start speaking German to me, his wife reprimanded him, and five minutes later he asked again, ‘Deutsch or English?’ It was an excursion organised by people from Breaking the Silence – Shovrim Shtika. Once on the bus, we were greeted by Yehuda Shaul, a former soldier.

A soldier in Hebron came up to me today and asked, ‘What’s your religion?’ Hebron began very early in the morning today. At 8.30 a.m. I stood across the street from Jerusalem’s Central Bus Station, waiting for a bus with a group of Canadians, Britons, a gay couple from Sweden, and a very elderly couple from Israel. They were so moving I couldn’t tear my eyes off them. Very elderly, around eighty, beautiful, when they said something to me, the gentleman always asked, ‘Deutsch or English?’ He would then forget my reply, start speaking German to me, his wife reprimanded him, and five minutes later he asked again, ‘Deutsch or English?’ It was an excursion organised by people from Breaking the Silence – Shovrim Shtika. Once on the bus, we were greeted by Yehuda Shaul, a former soldier.  Yehuda is one of the founders of the organisation – a group of former Israeli Army soldiers who have decided to talk about what the Israeli occupation really is. What it means to man a checkpoint for eight hours. What operation ‘friend’ means. What the tactic of ‘being present’ means in practice. How the Israeli army uses Palestinian children to avoid trouble when on patrol. Yehuda first told us how come that Breaking the Silence exists at all. It all started with a 2004 photo exhibition in which former soldiers, freshly back from a round in Hebron, wanted to show their everyday experiences in the army. Not the most shocking pictures. Rather those that were to simply inform about a reality so common for the soldiers that at some point they stopped paying attention to it. The impulse for organising the exhibit came from an inability to communicate those experiences in any other way, an inability to talk about it, a lack of proper language, of courage. Or perhaps above all the fact that the Israeli public doesn’t want to know. The mechanisms of repression are extremely effective. Such as a simple psychological method – the celebration of one’s own trauma. The Israeli public was shocked by the exhibition. The soldiers were taken to court. For what? For carrying out their orders.

Yehuda is one of the founders of the organisation – a group of former Israeli Army soldiers who have decided to talk about what the Israeli occupation really is. What it means to man a checkpoint for eight hours. What operation ‘friend’ means. What the tactic of ‘being present’ means in practice. How the Israeli army uses Palestinian children to avoid trouble when on patrol. Yehuda first told us how come that Breaking the Silence exists at all. It all started with a 2004 photo exhibition in which former soldiers, freshly back from a round in Hebron, wanted to show their everyday experiences in the army. Not the most shocking pictures. Rather those that were to simply inform about a reality so common for the soldiers that at some point they stopped paying attention to it. The impulse for organising the exhibit came from an inability to communicate those experiences in any other way, an inability to talk about it, a lack of proper language, of courage. Or perhaps above all the fact that the Israeli public doesn’t want to know. The mechanisms of repression are extremely effective. Such as a simple psychological method – the celebration of one’s own trauma. The Israeli public was shocked by the exhibition. The soldiers were taken to court. For what? For carrying out their orders.  Yehuda said something very important. ‘As a company commander, three, four months before discharge, I didn’t have much to do. So I sat and thought about what would happen to me. And I suddenly realised that I had lost all the arguments justifying what I had been doing for the last three years.’ Yehuda is a big, fattyish, strong guy. The kind of guy you’d gladly spend some time and go to a pub with. He has a lot of channelled energy in himself, a great deal of energy. And a kind of shadow. Hebron is the only Palestinian city in the West Bank with Jewish settlements in its very heart. In the light of international law, the settlements are illegal. In 1968, a year after the end of the Six Day War, when Israel gained control of Hebron, settlers came here and have never left the city since. The city saw two massacres. In 1929, Moslems killed 69 Jews and wounded a further 60. In 1994, Baruch Goldstein opened fire at Moslems praying in the Ibrahimi Mosque, killing 29 people. In 1997, in order to improve the safety of several hundred (600-800) settlers, the city was divided into two sectors – H1 and H2. The settlements are located in H2, where the Old Town, the Patriarch Tomb, and all that makes Hebron what it is are located. Some 30,000 Arabs live, or rather try to live, there, the remaining 120,000 in H2.

Yehuda said something very important. ‘As a company commander, three, four months before discharge, I didn’t have much to do. So I sat and thought about what would happen to me. And I suddenly realised that I had lost all the arguments justifying what I had been doing for the last three years.’ Yehuda is a big, fattyish, strong guy. The kind of guy you’d gladly spend some time and go to a pub with. He has a lot of channelled energy in himself, a great deal of energy. And a kind of shadow. Hebron is the only Palestinian city in the West Bank with Jewish settlements in its very heart. In the light of international law, the settlements are illegal. In 1968, a year after the end of the Six Day War, when Israel gained control of Hebron, settlers came here and have never left the city since. The city saw two massacres. In 1929, Moslems killed 69 Jews and wounded a further 60. In 1994, Baruch Goldstein opened fire at Moslems praying in the Ibrahimi Mosque, killing 29 people. In 1997, in order to improve the safety of several hundred (600-800) settlers, the city was divided into two sectors – H1 and H2. The settlements are located in H2, where the Old Town, the Patriarch Tomb, and all that makes Hebron what it is are located. Some 30,000 Arabs live, or rather try to live, there, the remaining 120,000 in H2.  In H2, Palestinian families are harassed on a daily basis by the settlers, who throw trash, excrements, disposable diapers, and all kinds of waste into their courtyards and onto the roofs of their houses. Jewish mamas teach their children how to throw stones at Arabs and tourists. The settlers’ violence verges on the hysterical. The Army doesn’t react. H2 is an apartheid system of roads – there are roads on which the Palestinians aren’t allowed at all, there are those where they can’t drive their cars, and those where they can’t open businesses. There also combinations of the three categories. The most tragic example is Al-Shuhada Street. A Jewish enclave closely guarded by an internal checkpoint. Just a couple of Palestinian families have endured there. Until recently they weren’t allowed to use the street, so their only connection with the world was the roof. The ban was recently lifted, but Yehuda says there are still streets that the Palestinians are not allowed to use at all. Such houses are small prisons. Their windows, doors, and balconies are barred, because the settlers smash the windows and pry open the doors almost every day. The Arabic Hebron is dying. Street after street is being crammed with massive concrete apartment blocks, shop after shop is being closed down. A ring of Jewish settlements is growing around the city. Four in ten Arab houses in downtown Hebron have been deserted, close to eight in ten Arab businesses – closed down.

In H2, Palestinian families are harassed on a daily basis by the settlers, who throw trash, excrements, disposable diapers, and all kinds of waste into their courtyards and onto the roofs of their houses. Jewish mamas teach their children how to throw stones at Arabs and tourists. The settlers’ violence verges on the hysterical. The Army doesn’t react. H2 is an apartheid system of roads – there are roads on which the Palestinians aren’t allowed at all, there are those where they can’t drive their cars, and those where they can’t open businesses. There also combinations of the three categories. The most tragic example is Al-Shuhada Street. A Jewish enclave closely guarded by an internal checkpoint. Just a couple of Palestinian families have endured there. Until recently they weren’t allowed to use the street, so their only connection with the world was the roof. The ban was recently lifted, but Yehuda says there are still streets that the Palestinians are not allowed to use at all. Such houses are small prisons. Their windows, doors, and balconies are barred, because the settlers smash the windows and pry open the doors almost every day. The Arabic Hebron is dying. Street after street is being crammed with massive concrete apartment blocks, shop after shop is being closed down. A ring of Jewish settlements is growing around the city. Four in ten Arab houses in downtown Hebron have been deserted, close to eight in ten Arab businesses – closed down.  Yehuda had managed to tell us all that before we arrived at the checkpoint and were stopped by the settlers, the police, the military, and the settlements’ own security agents. The barrier closed in front of the bus. Everyone took out their cameras. Yehuda filmed the policemen and was filmed by them, as well as by the settlers hurling abuse at him. Hour-long negotiations began, Yehuda’s nervous phone calls to lawyers, shouting, tension. Finally a decision was made – we can cross the checkpoint provided no one leaves the bus. If we do, we’ll be arrested. Okay. We decided to go, leave the bus and be arrested. The bus moved forward. The gate closed again, no one on the other side expected the decision. We stepped out and were immediately surrounded by settlers with a camera, shouting at us in Hebrew. None of us understood a word. Yehuda summarised it for us – they told him he was piece of shit and that Hebron was Jewish. His face was not a pleasant sight – tightened like a mask. When we were standing like that, suddenly a platform trailer appeared with a tank, a genuine, brand-new tank flying a big Israeli flag. No, they didn’t have the right to arrest us. But that’s how the execution of rights looks like in Israel. Military law means that decisions are made on the spot by the army, the given unit on site. Afterwards you can pursue your rights in court. We went elsewhere, but I’ll tell the story another time. Also about ‘operation friend,’ the tactic of ‘being present’ in Hebron, and how the army uses Palestinian children. Next morning I packed my backpack, went to the tiny Palestinian bus station and took a ‘service’ to a checkpoint near Bethlehem. My father has this saying, rather disgusting: if they throw you out through the door, come back through the window. The moment had obviously arrived on that day.

Yehuda had managed to tell us all that before we arrived at the checkpoint and were stopped by the settlers, the police, the military, and the settlements’ own security agents. The barrier closed in front of the bus. Everyone took out their cameras. Yehuda filmed the policemen and was filmed by them, as well as by the settlers hurling abuse at him. Hour-long negotiations began, Yehuda’s nervous phone calls to lawyers, shouting, tension. Finally a decision was made – we can cross the checkpoint provided no one leaves the bus. If we do, we’ll be arrested. Okay. We decided to go, leave the bus and be arrested. The bus moved forward. The gate closed again, no one on the other side expected the decision. We stepped out and were immediately surrounded by settlers with a camera, shouting at us in Hebrew. None of us understood a word. Yehuda summarised it for us – they told him he was piece of shit and that Hebron was Jewish. His face was not a pleasant sight – tightened like a mask. When we were standing like that, suddenly a platform trailer appeared with a tank, a genuine, brand-new tank flying a big Israeli flag. No, they didn’t have the right to arrest us. But that’s how the execution of rights looks like in Israel. Military law means that decisions are made on the spot by the army, the given unit on site. Afterwards you can pursue your rights in court. We went elsewhere, but I’ll tell the story another time. Also about ‘operation friend,’ the tactic of ‘being present’ in Hebron, and how the army uses Palestinian children. Next morning I packed my backpack, went to the tiny Palestinian bus station and took a ‘service’ to a checkpoint near Bethlehem. My father has this saying, rather disgusting: if they throw you out through the door, come back through the window. The moment had obviously arrived on that day.  I passed through the biggest checkpoint I had ever seen. Meanders of barriers, tonnes of concrete, steel turnstiles, bullet-proof windows, barrier systems. And the wall. This fragment of the wall is most spectacular. It seems taller than elsewhere, though it probably isn’t. So I passed through this labyrinth and on the other side Banksy’s mocking graffiti pictures welcomed me. As big as the wall and very cool. The second surprise were the smiles of the Palestinian taxi drivers waiting for schlemiels like me. Because on shabbat, even though it’s a Jewish holiday, the service to the checkpoint on the other side of the wall is closed. I started to negotiate.

I passed through the biggest checkpoint I had ever seen. Meanders of barriers, tonnes of concrete, steel turnstiles, bullet-proof windows, barrier systems. And the wall. This fragment of the wall is most spectacular. It seems taller than elsewhere, though it probably isn’t. So I passed through this labyrinth and on the other side Banksy’s mocking graffiti pictures welcomed me. As big as the wall and very cool. The second surprise were the smiles of the Palestinian taxi drivers waiting for schlemiels like me. Because on shabbat, even though it’s a Jewish holiday, the service to the checkpoint on the other side of the wall is closed. I started to negotiate.  ‘Two hundred shekels. Two ways – to Hebron and back.’ ‘No way.’ I decided to play it tough. ‘You know how much gasoline…’ ‘No way. From Ramallah to Jenin is two hours and I paid 200. How long does it take to go to Hebron? 30 minutes?’ – I understated the price to Jenin, but I knew that the very word ‘Jenin’ was like a magical key. I was right. ‘Okay, one hundred and fifty and I can wait for you two hours in Hebron.’ I looked at the guy and I liked him. ‘Okay. Seventy five one way. Alright.’ I made friends with him on the way. His name was Tareq. He was all happy when it turned out I knew about Aroup Refugee Camp, which we passed on the way.

‘Two hundred shekels. Two ways – to Hebron and back.’ ‘No way.’ I decided to play it tough. ‘You know how much gasoline…’ ‘No way. From Ramallah to Jenin is two hours and I paid 200. How long does it take to go to Hebron? 30 minutes?’ – I understated the price to Jenin, but I knew that the very word ‘Jenin’ was like a magical key. I was right. ‘Okay, one hundred and fifty and I can wait for you two hours in Hebron.’ I looked at the guy and I liked him. ‘Okay. Seventy five one way. Alright.’ I made friends with him on the way. His name was Tareq. He was all happy when it turned out I knew about Aroup Refugee Camp, which we passed on the way.  So we wandered around Hebron together. He took me to the mosque with the graves of Abraham, Sarah and Isaac. Then we went towards the Jewish enclave. Barriers, turnstiles, concrete. Two soldiers for a start. One had a very tired face. He held his M16 as if he was holding a child, but that child was obviously an immense burden for him. Questions, questions. Poland, no, no press. Okay, go. We keep walking, a dead town, the Arab shops boarded up, more concrete barriers, watchtowers, camouflage nets. A battlefield. Not a person in sight. I suddenly burst out laughing. In front of the closed gates of the post-Arab shops flowers had been planted, some kind of climbing plants, which had already managed to cover several gates. How pretty and aesthetic. Obviously the inhabitants could not bear the sight of emptiness. Suddenly a commotion. The police, the military. Tareq has to present his ID. They say Palestinians aren’t allowed here. Okay, but we had been let through, I say. An unpleasant situation, I suddenly got frightened they’d arrest him. They sent the poor guy with a tired face that had let us through for us. Escorted by the M16 we walked back.

So we wandered around Hebron together. He took me to the mosque with the graves of Abraham, Sarah and Isaac. Then we went towards the Jewish enclave. Barriers, turnstiles, concrete. Two soldiers for a start. One had a very tired face. He held his M16 as if he was holding a child, but that child was obviously an immense burden for him. Questions, questions. Poland, no, no press. Okay, go. We keep walking, a dead town, the Arab shops boarded up, more concrete barriers, watchtowers, camouflage nets. A battlefield. Not a person in sight. I suddenly burst out laughing. In front of the closed gates of the post-Arab shops flowers had been planted, some kind of climbing plants, which had already managed to cover several gates. How pretty and aesthetic. Obviously the inhabitants could not bear the sight of emptiness. Suddenly a commotion. The police, the military. Tareq has to present his ID. They say Palestinians aren’t allowed here. Okay, but we had been let through, I say. An unpleasant situation, I suddenly got frightened they’d arrest him. They sent the poor guy with a tired face that had let us through for us. Escorted by the M16 we walked back.  ‘How many setters live here? I asked even though I knew the answer. ‘Seven hundred or so.’ Silence. Then he asks. ‘How many Palestinians?’ ‘150,000-160,000.; ‘So you see.’ ‘I see.’ ‘Must be very hard to serve here.’ ‘Terribly hard.’ He lowered his head.

‘How many setters live here? I asked even though I knew the answer. ‘Seven hundred or so.’ Silence. Then he asks. ‘How many Palestinians?’ ‘150,000-160,000.; ‘So you see.’ ‘I see.’ ‘Must be very hard to serve here.’ ‘Terribly hard.’ He lowered his head.  He was just a kid with a light face. It was clear it all hurt him very much. If he could, he’d be screaming. I entered the next Jewish enclave alone – it was the famous Al-Shuhada Street. Stones flew towards me. The soldiers stood nearby. They didn’t react. I need a break from this torrent of misfortune because I’m losing my ability to write. I need to leave here. May 7, 2008

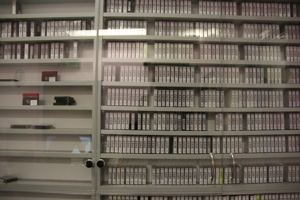

He was just a kid with a light face. It was clear it all hurt him very much. If he could, he’d be screaming. I entered the next Jewish enclave alone – it was the famous Al-Shuhada Street. Stones flew towards me. The soldiers stood nearby. They didn’t react. I need a break from this torrent of misfortune because I’m losing my ability to write. I need to leave here. May 7, 2008  Jerusalem is all fireworks today – it’s Independence Day. I’m sitting at Palm Hostel, explosions outside my window, listening to Wissam Murad. A guy from Jerusalem. Great music. The rhythm is set by firecrackers and bangers though… More on that in a moment. B’Tselem sent me an official apology. They must have thought hard for two days if they wrote, ‘The matter seemed to have created a small internal debate – it is a bit of a unique case for us because most of the footage requests we get are more TV, news oriented, with a less clear political purpose.’ Put shortly, I’m returning there next week. Great. I was at the ICAHD today [Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions]. The ICAHD deals with all cases of house demolitions. And it has a lot to deal with – since 1967 the Israelis have razed to the ground 18,000 Palestinian houses, of which the ICAHD activists have managed to rebuild 106 over the last 10 years. That’s not much. Especially that the bulldozers sometimes demolish again the houses that have been rebuilt with the joint effort of the ICAHD activists and voluntaries. It’s hard to fight the official policy of your own state, one of the guidelines of which is to reduce the number of Palestinians living in areas earmarked for Jewish settlement or in their vicinity. Today, as I’ve read, there are 5,499,000 Jews in Israel and 1,461,000 Arabs (20 percent). The demographic race continues. To my eye, the Arabs breed faster.

Jerusalem is all fireworks today – it’s Independence Day. I’m sitting at Palm Hostel, explosions outside my window, listening to Wissam Murad. A guy from Jerusalem. Great music. The rhythm is set by firecrackers and bangers though… More on that in a moment. B’Tselem sent me an official apology. They must have thought hard for two days if they wrote, ‘The matter seemed to have created a small internal debate – it is a bit of a unique case for us because most of the footage requests we get are more TV, news oriented, with a less clear political purpose.’ Put shortly, I’m returning there next week. Great. I was at the ICAHD today [Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions]. The ICAHD deals with all cases of house demolitions. And it has a lot to deal with – since 1967 the Israelis have razed to the ground 18,000 Palestinian houses, of which the ICAHD activists have managed to rebuild 106 over the last 10 years. That’s not much. Especially that the bulldozers sometimes demolish again the houses that have been rebuilt with the joint effort of the ICAHD activists and voluntaries. It’s hard to fight the official policy of your own state, one of the guidelines of which is to reduce the number of Palestinians living in areas earmarked for Jewish settlement or in their vicinity. Today, as I’ve read, there are 5,499,000 Jews in Israel and 1,461,000 Arabs (20 percent). The demographic race continues. To my eye, the Arabs breed faster.  I am reminded of Yael Bartana’s film documenting the reconstruction of one of such houses. Smiling faces, eyes full of hope, heroic poses, the figures shown from below. That’s how the builders of the state of Israel in the 1950s looked like. It’d be interesting to know whether the house rebuilt that summer and filmed by Bartana got demolished by Israeli bulldozers again too. The viewers leave the projection room fortified that the wave is returning, that Israel, with the hands of its activists, is rebuilding Palestinian homes. Asked about the systematic house demolitions in eastern Jerusalem, the city’s mayor replies evasively, ‘As you know perfectly well, the Palestinian population is growing, not shrinking.’ The ICAHD doesn’t know when or where a house is to be demolished. Quite simply, early in the morning, Israeli police and Border Guard personnel gather at a chosen location accompanied by government bulldozers. The police surround the house. Jeff Halper, the ICAHD coordinator, told me in detail how the operation looks like: demolishing a small house takes 20 minutes, a big one – up to two hours. No one informs the inhabitants about the operation – neither the city authorities, nor the Ministry of Internal Affairs, nor the local administration. Tens of thousands of families live in fear of the bulldozers, 22,000 of which in Jerusalem itself. This is in fact a violation of the 4th Geneva Convention (Article 53), which prohibits the demolition of houses in occupied territories. It’s only that Israel does not observe the 4th Geneva Convention. During a recent demolition, Jeff Halper, citing the Convention, ordered a Border Guard officer arrested. He only provoked bursts of laughter and was himself handcuffed. I’d like to film a house demolition. I don’t know whether I can get there on time but I’ll try. If not, I’ll use footage from the ICAHD or B’Tselem.

I am reminded of Yael Bartana’s film documenting the reconstruction of one of such houses. Smiling faces, eyes full of hope, heroic poses, the figures shown from below. That’s how the builders of the state of Israel in the 1950s looked like. It’d be interesting to know whether the house rebuilt that summer and filmed by Bartana got demolished by Israeli bulldozers again too. The viewers leave the projection room fortified that the wave is returning, that Israel, with the hands of its activists, is rebuilding Palestinian homes. Asked about the systematic house demolitions in eastern Jerusalem, the city’s mayor replies evasively, ‘As you know perfectly well, the Palestinian population is growing, not shrinking.’ The ICAHD doesn’t know when or where a house is to be demolished. Quite simply, early in the morning, Israeli police and Border Guard personnel gather at a chosen location accompanied by government bulldozers. The police surround the house. Jeff Halper, the ICAHD coordinator, told me in detail how the operation looks like: demolishing a small house takes 20 minutes, a big one – up to two hours. No one informs the inhabitants about the operation – neither the city authorities, nor the Ministry of Internal Affairs, nor the local administration. Tens of thousands of families live in fear of the bulldozers, 22,000 of which in Jerusalem itself. This is in fact a violation of the 4th Geneva Convention (Article 53), which prohibits the demolition of houses in occupied territories. It’s only that Israel does not observe the 4th Geneva Convention. During a recent demolition, Jeff Halper, citing the Convention, ordered a Border Guard officer arrested. He only provoked bursts of laughter and was himself handcuffed. I’d like to film a house demolition. I don’t know whether I can get there on time but I’ll try. If not, I’ll use footage from the ICAHD or B’Tselem.  Yesterday I visited an exhibition at the Museum on the Seam, an institution focused on socio-political art. The Museum on the Seam is called so because it is located at a street that separates eastern Jerusalem from western Jerusalem. The house where it is located has participated in every armed conflict to date. It’s a miracle it still stands. I hadn’t seen any art for so long that I felt a pleasant thrill. I realised I didn’t remember when was the last time I participated in a serious exhibition. I think it was six years ago, at Casino Luxembourg, even before the palm. The show has a nice title – Bare Life. As I read, it pointed to ‘the dangerous place where a temporary emergency situation can be turned into a legitimised status quo accepted by the silent majority.’ Many well-known names, including three from Poland – Wilhelm Sasnal, Katarzyna Józefowicz and Artur Żmijewski, that is, the FGF key. Plus, among others, Bruce Nauman, Anselm Kiefer, Carsten Höller, and even Samuel Beckett himself. Most of the visitors were American tourists, which was painful because they were very loud.

Yesterday I visited an exhibition at the Museum on the Seam, an institution focused on socio-political art. The Museum on the Seam is called so because it is located at a street that separates eastern Jerusalem from western Jerusalem. The house where it is located has participated in every armed conflict to date. It’s a miracle it still stands. I hadn’t seen any art for so long that I felt a pleasant thrill. I realised I didn’t remember when was the last time I participated in a serious exhibition. I think it was six years ago, at Casino Luxembourg, even before the palm. The show has a nice title – Bare Life. As I read, it pointed to ‘the dangerous place where a temporary emergency situation can be turned into a legitimised status quo accepted by the silent majority.’ Many well-known names, including three from Poland – Wilhelm Sasnal, Katarzyna Józefowicz and Artur Żmijewski, that is, the FGF key. Plus, among others, Bruce Nauman, Anselm Kiefer, Carsten Höller, and even Samuel Beckett himself. Most of the visitors were American tourists, which was painful because they were very loud.  I couldn’t resist the impression that it was yet another manifestation suggesting that Israel is a fully democratic state that, go ahead, please, permits critical statements about the most controversial issue – Israeli apartheid. And as a disguise, to universalise the problem and blur it, the main course was accompanied by hors d’oeuvres in the form of all kinds of other apartheids, oppressions, reprisals, traumas, holocausts, disasters and general misfortunes. Art sometimes works despite, and sometimes instead. I experienced half an hour of genuine joy there. And that was thanks to Wilhelm Sasnal and several other artists. I didn’t notice Sasnal’s name on the list of the participating artists. From the corner of my eye I saw I beautiful painting on the wall. I fixed my gaze on it and was transfixed. Black-and-white, simple, incredible. Four or five women going through a mountain pass, the time is twilight. The women are shown from the back, the light is in front, ahead of them, mountains in the distance. They have scarves on their heads and carry some bags, handbags, stuff, though not too much. They are kind of walking, kind of standing. Everything was in that picture – trauma and fear of the unknown, uncertainty, femininity, weakness. They could have been Arab women at a checkpoint as well as lost tourists in the Tatras. The painting was untitled and that was nice, the question mark – who and what and why. Wilhelm, if you read this blog, please accept my best compliments. I had shivers down my spine.

I couldn’t resist the impression that it was yet another manifestation suggesting that Israel is a fully democratic state that, go ahead, please, permits critical statements about the most controversial issue – Israeli apartheid. And as a disguise, to universalise the problem and blur it, the main course was accompanied by hors d’oeuvres in the form of all kinds of other apartheids, oppressions, reprisals, traumas, holocausts, disasters and general misfortunes. Art sometimes works despite, and sometimes instead. I experienced half an hour of genuine joy there. And that was thanks to Wilhelm Sasnal and several other artists. I didn’t notice Sasnal’s name on the list of the participating artists. From the corner of my eye I saw I beautiful painting on the wall. I fixed my gaze on it and was transfixed. Black-and-white, simple, incredible. Four or five women going through a mountain pass, the time is twilight. The women are shown from the back, the light is in front, ahead of them, mountains in the distance. They have scarves on their heads and carry some bags, handbags, stuff, though not too much. They are kind of walking, kind of standing. Everything was in that picture – trauma and fear of the unknown, uncertainty, femininity, weakness. They could have been Arab women at a checkpoint as well as lost tourists in the Tatras. The painting was untitled and that was nice, the question mark – who and what and why. Wilhelm, if you read this blog, please accept my best compliments. I had shivers down my spine.  On the roof was a swing mounted to the railing – a work by Carsten Höller. Cool. Light. I looked down. An exclusively orthodox playground. Jewish mamas, nannies and children. It looked like an exhibition piece, superbly thought-out, an interactive installation. And how very political. Only it was far more powerful than all the works shown in Bare Life. Or perhaps I’m infected. Perhaps I strayed too far. I lost my faith in the political effectiveness of such exhibitions. Rebuilding a house with the ICAHD probably makes more sense. Viewing the show I kept thinking about the Bad Boys from Jenin. About how they’d react to it. What they’d like. What they’d laugh at. What they’d compare it to. What they’d understand. I bought myself a nice T-shirt saying ‘Bare Life.’ A bit too large.

On the roof was a swing mounted to the railing – a work by Carsten Höller. Cool. Light. I looked down. An exclusively orthodox playground. Jewish mamas, nannies and children. It looked like an exhibition piece, superbly thought-out, an interactive installation. And how very political. Only it was far more powerful than all the works shown in Bare Life. Or perhaps I’m infected. Perhaps I strayed too far. I lost my faith in the political effectiveness of such exhibitions. Rebuilding a house with the ICAHD probably makes more sense. Viewing the show I kept thinking about the Bad Boys from Jenin. About how they’d react to it. What they’d like. What they’d laugh at. What they’d compare it to. What they’d understand. I bought myself a nice T-shirt saying ‘Bare Life.’ A bit too large.  So I’m sitting in this T-shirt a Palm Hostel. The anniversary celebrations are under way. Jaffa Road and Ben Yehuda surrounded by the military, police, plainclothes agents. Damn military celebrations… Among the souvenirs are swords, inflatable hammers and Star-of-David baseball bats. I tried to imagine an inflatable baseball bat with a Polish flag. Ouch. Some amused old guy hit me on the head with a bat like that.

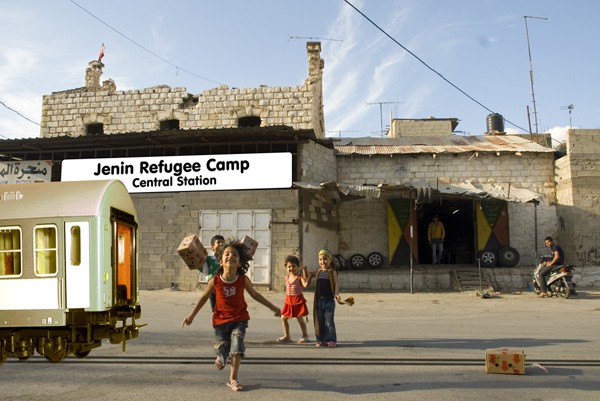

So I’m sitting in this T-shirt a Palm Hostel. The anniversary celebrations are under way. Jaffa Road and Ben Yehuda surrounded by the military, police, plainclothes agents. Damn military celebrations… Among the souvenirs are swords, inflatable hammers and Star-of-David baseball bats. I tried to imagine an inflatable baseball bat with a Polish flag. Ouch. Some amused old guy hit me on the head with a bat like that.  The West Bank is inaccessible. The checkpoints have been closed due to the celebrations. Israel has to celebrate the 60th anniversary of its democratic state in peace, after all. It will be even worse next week, even more military and police – George W. Bush, Tony Blair, Henry Kissinger, Mikhail Gorbachev, Rupert Murdoch and the founders of Google and Facebook are due in Jerusalem. May 1, 2008 Three days and one night in solitude, spent on writing, brought me to a state of complete incorporeality. I know this condition, I have to stand up, touch my cheek, reach out with my hand backwards and feel my shoulder blade to remind myself that I exist at all. Looking into the mirror works too, though the reflection is incorporeal. I went yesterday to the cake shop where I used the spent the evenings with the guys – Nabeel, Żwirek, Mustafa, Mike and Tarek. They are all gone now. They love glow tubes in the Middle East so we sat under an extremely white glow tube and a howling fan. There was a baldish palm tree outside and still, hot air. I ordered tea, the lousy Lipton, because that’s all they’ve got, and some kind of cheese cake, and reached for a book, but I couldn’t even get through a single page. Arab bankers in ugly suits sat next to me, doing business. Gel-styled hair, pointed-toe shoes. I looked at a poster with an image of Edward Said, the father of post-colonial theories, and I felt I was in the right place, not besides but right here. Only that ‘here’ remained a strange place for me. From time to time I walk down from my big, empty four-room flat with a large kitchen to the theatre office, where Juliano asks me ceremonially, ‘Joanna, where are you hiding?’ to which I reply equally ceremonially, ‘I’m not hiding, I’m working.’ Then I walk rigidly to the shop, where the shopkeeper asks me, ‘Humus?’ ‘Humus,’ I reply ‘Pita?’ ‘Pita,’ I confirm, and with the humus, pita and a bottle of grapefruit juice I walk back with the same rigid gait to my cave. When I’m seventy it’ll probably still be the same. I’ll be living in Ghana, ferociously fighting for some refugees’ rights and earning my living designing websites. A wheelchair waiting in the hall. I’ll be even skinnier and my hearing will be even worse. Yeah, a retreat like this makes you realise many things. For instance that in order to have my film edited in a professional manner I should earn some money to pay an editor. I earned for my stay here and Żwirek’s visit. I earned for the camera. This leaves editing. The funniest thing is that I don’t have where to show this film. I’ll probably soon read on some web forum that I’m wasting public funds on suspicious trips. I’ve managed to put a certain intuition into writing; it even has a title, Jenin Refugee Camp Central Station – a five-day street performance. But before the project had been described in detail, it grew and I lost control of it.

The West Bank is inaccessible. The checkpoints have been closed due to the celebrations. Israel has to celebrate the 60th anniversary of its democratic state in peace, after all. It will be even worse next week, even more military and police – George W. Bush, Tony Blair, Henry Kissinger, Mikhail Gorbachev, Rupert Murdoch and the founders of Google and Facebook are due in Jerusalem. May 1, 2008 Three days and one night in solitude, spent on writing, brought me to a state of complete incorporeality. I know this condition, I have to stand up, touch my cheek, reach out with my hand backwards and feel my shoulder blade to remind myself that I exist at all. Looking into the mirror works too, though the reflection is incorporeal. I went yesterday to the cake shop where I used the spent the evenings with the guys – Nabeel, Żwirek, Mustafa, Mike and Tarek. They are all gone now. They love glow tubes in the Middle East so we sat under an extremely white glow tube and a howling fan. There was a baldish palm tree outside and still, hot air. I ordered tea, the lousy Lipton, because that’s all they’ve got, and some kind of cheese cake, and reached for a book, but I couldn’t even get through a single page. Arab bankers in ugly suits sat next to me, doing business. Gel-styled hair, pointed-toe shoes. I looked at a poster with an image of Edward Said, the father of post-colonial theories, and I felt I was in the right place, not besides but right here. Only that ‘here’ remained a strange place for me. From time to time I walk down from my big, empty four-room flat with a large kitchen to the theatre office, where Juliano asks me ceremonially, ‘Joanna, where are you hiding?’ to which I reply equally ceremonially, ‘I’m not hiding, I’m working.’ Then I walk rigidly to the shop, where the shopkeeper asks me, ‘Humus?’ ‘Humus,’ I reply ‘Pita?’ ‘Pita,’ I confirm, and with the humus, pita and a bottle of grapefruit juice I walk back with the same rigid gait to my cave. When I’m seventy it’ll probably still be the same. I’ll be living in Ghana, ferociously fighting for some refugees’ rights and earning my living designing websites. A wheelchair waiting in the hall. I’ll be even skinnier and my hearing will be even worse. Yeah, a retreat like this makes you realise many things. For instance that in order to have my film edited in a professional manner I should earn some money to pay an editor. I earned for my stay here and Żwirek’s visit. I earned for the camera. This leaves editing. The funniest thing is that I don’t have where to show this film. I’ll probably soon read on some web forum that I’m wasting public funds on suspicious trips. I’ve managed to put a certain intuition into writing; it even has a title, Jenin Refugee Camp Central Station – a five-day street performance. But before the project had been described in detail, it grew and I lost control of it.  Not far from the theatre, on the way to Juliano and Jenny’s house, is a small square. We went to the butcher’s there. Next to the butcher’s is a small grocery store, a car repair garage in front of which sits an old, red-haired man on a wheelchair, and a carpenter’s. The carpenter’s shop is in an annex to a large, strange stone building. People told me it was an old Turkish train station from the Ottoman times. ‘Turkiye, Turkiye,’ they kept repeating. And here, right under your feet, is the rail track, added Jonathan. I felt shivers down my spine. I suddenly saw in my mind’s eye the image of a welcoming orchestra, flowers, the whole hullabaloo and joyful chaos accompanying the departures and returns from holidays. That was some two weeks ago. Now I went there to take some photos and montage into a picture of the station the following simple inscription: Jenin Refugee Camp Central Station, and juxtapose a railroad car with that. The car is Polish, but so what, a small gesture of Polish solidarity with the victims of occupation.

Not far from the theatre, on the way to Juliano and Jenny’s house, is a small square. We went to the butcher’s there. Next to the butcher’s is a small grocery store, a car repair garage in front of which sits an old, red-haired man on a wheelchair, and a carpenter’s. The carpenter’s shop is in an annex to a large, strange stone building. People told me it was an old Turkish train station from the Ottoman times. ‘Turkiye, Turkiye,’ they kept repeating. And here, right under your feet, is the rail track, added Jonathan. I felt shivers down my spine. I suddenly saw in my mind’s eye the image of a welcoming orchestra, flowers, the whole hullabaloo and joyful chaos accompanying the departures and returns from holidays. That was some two weeks ago. Now I went there to take some photos and montage into a picture of the station the following simple inscription: Jenin Refugee Camp Central Station, and juxtapose a railroad car with that. The car is Polish, but so what, a small gesture of Polish solidarity with the victims of occupation.  The performance would require some technical preparations – laying some 300 metres of tracks, bringing an old railroad car from Jordan or Israel, installing ‘Platform 1,’ ‘Platform 2′ etc. plaques and stands. When everything is ready, the kids from the theatre will become passengers, conductors, luggage porters. I imagine them getting out of the car, in their sunglasses, carrying all those suitcases and backpacks, the band plays, the loudspeakers announce a train to Warsaw departing in five minutes’ time, stopping at: Amman, Damascus, Istanbul, Sophia, Bucharest, Bratislava, Cracow… And we roll the car from the square. People will first want to go to Haifa, their home town, Juliano notices soberly in an e-mail (we are e-mailing each other from a distance of 50 metres – I am in my apartment, he at the theatre downstairs). They will decide themselves where they want to go, the performance will be an open formula, I reply.

The performance would require some technical preparations – laying some 300 metres of tracks, bringing an old railroad car from Jordan or Israel, installing ‘Platform 1,’ ‘Platform 2′ etc. plaques and stands. When everything is ready, the kids from the theatre will become passengers, conductors, luggage porters. I imagine them getting out of the car, in their sunglasses, carrying all those suitcases and backpacks, the band plays, the loudspeakers announce a train to Warsaw departing in five minutes’ time, stopping at: Amman, Damascus, Istanbul, Sophia, Bucharest, Bratislava, Cracow… And we roll the car from the square. People will first want to go to Haifa, their home town, Juliano notices soberly in an e-mail (we are e-mailing each other from a distance of 50 metres – I am in my apartment, he at the theatre downstairs). They will decide themselves where they want to go, the performance will be an open formula, I reply.  That was yesterday. Today I went down to the office (walking rigidly, on my way for some pita and humus) and it suddenly turned out that the project had already undergone numerous modifications and alterations. ‘We’ll lay real tracks,’ said Juliano, ‘the small-gauge ones. Through the whole camp and down to the town.’ ‘We can create stations in the camp, prepare charts and photos showing what happened there,’ added Mussadak, the accountant, who never speaks. ‘Adnan, you will build the locomotive, or at least an engine,’ said Juliano. ‘No problem, Adnan has just repaired some batteries.’ ‘It’ll take us two years to get the permissions,’ I moaned. ‘Here? In the camp? No way, one word from Zacharia and it’s done.’

That was yesterday. Today I went down to the office (walking rigidly, on my way for some pita and humus) and it suddenly turned out that the project had already undergone numerous modifications and alterations. ‘We’ll lay real tracks,’ said Juliano, ‘the small-gauge ones. Through the whole camp and down to the town.’ ‘We can create stations in the camp, prepare charts and photos showing what happened there,’ added Mussadak, the accountant, who never speaks. ‘Adnan, you will build the locomotive, or at least an engine,’ said Juliano. ‘No problem, Adnan has just repaired some batteries.’ ‘It’ll take us two years to get the permissions,’ I moaned. ‘Here? In the camp? No way, one word from Zacharia and it’s done.’  If you have never visited a Palestinian refugee camp, you don’t know what it means not to be able to go anywhere. It’s like putting someone inside a glass jar and sealing the lid. Going to Ramallah is like bouncing off a glass wall. Words like ‘travel,’ ‘space,’ ‘sea,’ ‘train’ act like fuses, making present that which has been lawlessly taken away from you. That’s probably why Juliano says that if the project gets through, a revolution will begin here. 5.05.08

If you have never visited a Palestinian refugee camp, you don’t know what it means not to be able to go anywhere. It’s like putting someone inside a glass jar and sealing the lid. Going to Ramallah is like bouncing off a glass wall. Words like ‘travel,’ ‘space,’ ‘sea,’ ‘train’ act like fuses, making present that which has been lawlessly taken away from you. That’s probably why Juliano says that if the project gets through, a revolution will begin here. 5.05.08  ‘The Hasidim walk like this,’ Leslie thrusts her chest forward, throws the right leg forward, very quickly, the steps are small, it’s almost like waddling, then the left leg, then the right, the left, the right, she waves her arms to the rhythm, with full control, not too high. And she pushes forward, her upper body leaning aggressively, cutting through the air. Then she stops and bursts out laughing. ‘And their dress, the frock coats, the tails flapping in the wind, the fur hats. It’s not easy to push through the air dressed like that.’ ‘We should do a project about it. About how the Arabs walk – slumped, stooped, scowling at you, and then the Hasidim – straight like sticks, kind of pushed forward.’ We live in neighbouring hostels in Eastern Jerusalem, crowds teem in the Arab shops below. If you buy little, they get angry and raise the price. One lemon is three shekels, the same as two lemons and five courgettes. We both came from the theatre, using slightly different routes and for different purposes. Chance brought us together again.